THE MAN WHO LIVED wITH MONSTERS

by Tacey M. Atsitty

Indigenous Fiction Prize Finalist

His walk had become calm, and now it was almost a stagger. He drank but had not eaten or moved in days, and now to see him lift himself from the fire’s side and to hear the soft crackle of his knees was hard to bear. This was the only time in his life he’d been allowed inside. The small crunch of snow from his paws came gradually and matched the short clouds of breath that left his mouth. Into the thick of pinion pine, he quivered—

He’ll climb the hill slowly until he can no longer push through the fallen snow, until he reaches where he is going. Don’t go after them. They know when it’s time; you just let them go, the old man’s nálí used to tell him.

* * *

My grandpa would tell me, “That’s the way you shouldn’t interfere with life. That’s the way life pushes on, even if you’re not sure where you’re going.” The man pulls out another can from under the table. It’s been cold enough in the hogan that he no longer needs to tuck them in the snow. It’s been two weeks since his relatives came to check on him. Two weeks since he’s spoken aloud. Now that Pubbytsoh is gone, he feels the need to speak out loud, even if no one is around. He thinks of his woodpile outside the door, and how the wind’s whittling it to tinder, thin strands of cedar bark wafting, like his hair.

Kindling doesn’t matter if it has nothing to keep it fire, when it’s not ready to go.

When did these hands wrinkle into ghost beads? He grips the can with his left hand and taps the top with his right fingertips before slowly lifting it to his mouth then blows softly. It’s an awkward grip. The knots at his knuckles protrude as if they weren’t even part of the hand, as if they belonged to a thick chunk of firewood.

Before I left, there was this girl from Rock Point. She liked to pick berries, brought me a ring of dried cedar berries to wear. He sets the can aside for a moment and scans his home. In the middle of the round house is a wood-burning stove, old with the beginnings of rust but without creosote. In its belly dims the last of his coal, and atop sits a pot of watery macaroni with bits of Spam swimming in it. At one end of his home is a small shelf made of two-by-fours holding a near-empty box of oatmeal, a cylinder of sugar, ground coffee, a few dishes, and a sack with a lone potato that has gone crazy with sprouts. At the other end is a metal box-spring bed with a polyester bedspread. He smiles as he remembers the squeaks it came to make by that girl from Rock Point not long after he arrived back from—. His eyes begin to water lightly for marrying her, then leaving her only a day later.

On the walls hang photos of his nephews in uniform and nieces in rug dresses at graduation. The photos are half-covered by two small American flags, nearly faded all to white. He slides his feet across the dirt floor as far as his knees can extend; it is hard and will be for sometime longer. He thinks how the crumbles of red dirt from beneath his shoes look like sumac berries and he remembers how, as a child, his mother would make him chił chin, how even though he would say nothing, she knew it was his favorite.

He picks up the can again and blows at it as though it were a cup of steaming pudding. He thinks of cedar berries, hollowed out to string into necklaces or bracelets, how they once were juicy and plump.

Now they’ve gone loose with wrinkle and hardened like wood, yet still so empty. Grandpa told me war was part of life; it had to be and always was for the Diné.

I’ve come to be like the pull-tab of this can. The man pulls the tab open and it pops. A tongue bent downward, allowing everything to gush out, keeping only the residue.

Maybe I’d feel better if I don’t go. The man takes a sip. Guam wasn’t the only place that he’d lose so much. He thinks of that island, that jungle still lightly lit inside him. He swallows and swallows.

He senses someone standing near him.

It didn’t matter your age, there will always be an enemy. His ears perk as he hears a gentle whirring outside, a sound he hasn’t heard in years. The sound spurs him into a trance. Pop! Pop! They’re shooting the enemy! He makes a grab for his gun but finds only the leg of his chair. His rifle sits against the wall, next to the door. It was the Enemy Way that helped him when he got back. He stands up slowly. His knees wobble gently, but he makes his way to the door. He fondles his .270 before stepping outside. I went to fight monsters just like Naayéé’ Neezghání did.

Everything is still the same: the ground, the trees, the snow, the wind, the tracks, everything. The old man begins to walk down the mountain. He looks up at the clouds but doesn’t watch for too long.

Soon he will battle a blizzard. He passes through ridges of snowdrift; they collapse like clouds of smoke. He hears snow settling somewhere and steadies the rifle to his chest, his trigger finger ready. He knows the enemy is there— He scans the perimeter then lowers his weapon. He tries to pick up his pace but isn’t able to, so he barricades himself in a small crevice on the side of the mountain. He goes to the trees and breaks off twigs and shakes fallen branches of their old snow.

The snow begins again. He grows closer to the fire he’s made and begins to think. He thinks of his fields overgrown with sagebrush. He rethinks his policy on not allowing dogs in the hogan. He remembers finding a string of beads under a juniper tree where he’d sit under while herding sheep in summers. With his fingers, he traces every switchback down the mountain; they’re barely visible now, but he knows those trails like old friends.

He thanks his loneliness all these years, for comforting him.

He recalls a Creation Story; and begins to cry for the monsters who as infants were abandoned by their mothers. He wonders how they survived. Later in their lives most were killed off, but Changing Woman left a few to pester the people, so that they’d remember. He recalls their names— now he sees them clearer than ever— in his hands, in the cavity of his stomach, in the belly of his wood stove. Water Monster was the first he had seen; that was overseas. The monster had cradled him on the big waters. And he wondered when the rest had crept up on him, how he allowed snow to drift that far inside him, how he had come to keep the company of monsters, allowing them to embrace him and breathe in from his every swirl until his toes, fingertips, and head wound black.

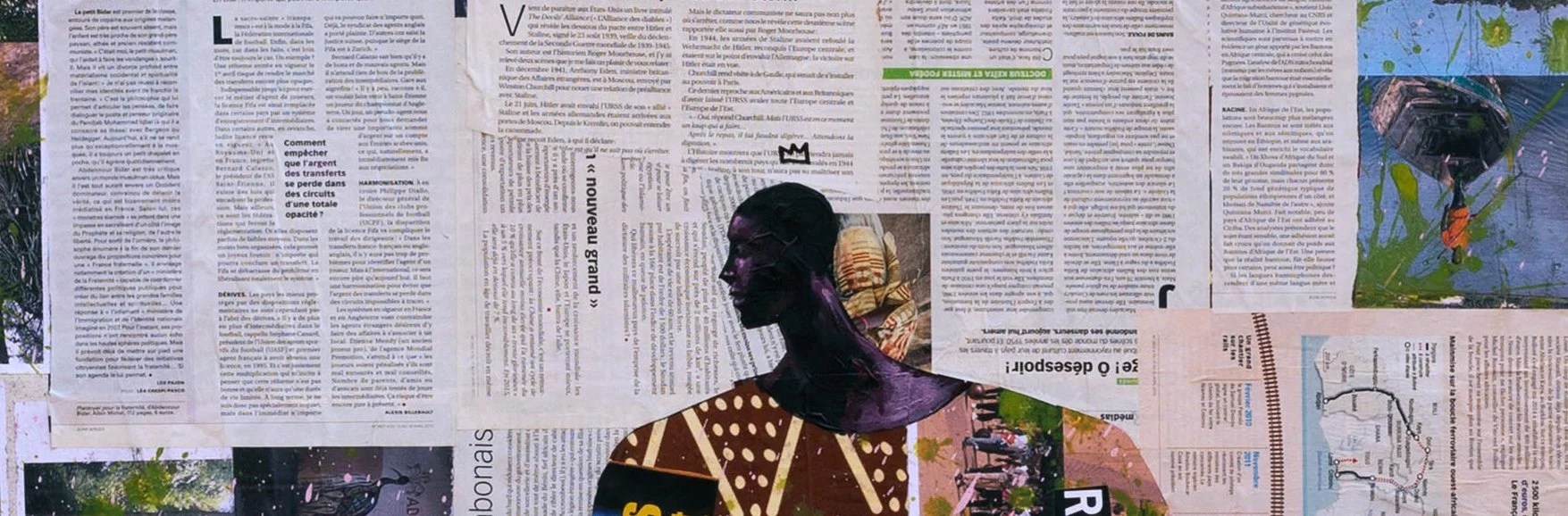

Detail of artwork by Aluu Prosper Chigozie

Tacey M. Atsitty, Diné (Navajo), is Tsénahabiłnii (Sleep Rock People) and born for Ta'neeszahnii (Tangle People). Atsitty is a recipient of the Wisconsin Brittingham Prize for Poetry and other prizes. Her work has appeared in POETRY; EPOCH; Kenyon Review Online; Prairie Schooner; Leavings, and other publications. Her first book is Rain Scald (University of New Mexico Press, 2018), and her second book is (At) Wrist (University of Wisconsin Press, 2023). She has a PhD in Creative Writing from Florida State University and is Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Beloit College in Wisconsin.