Interview with Chris Hoshnic, Chapter House Journal Editor-in-Chief, on Crossing Genres from Poetry to Playwriting and Beyond

by Rey M. Rodríguez

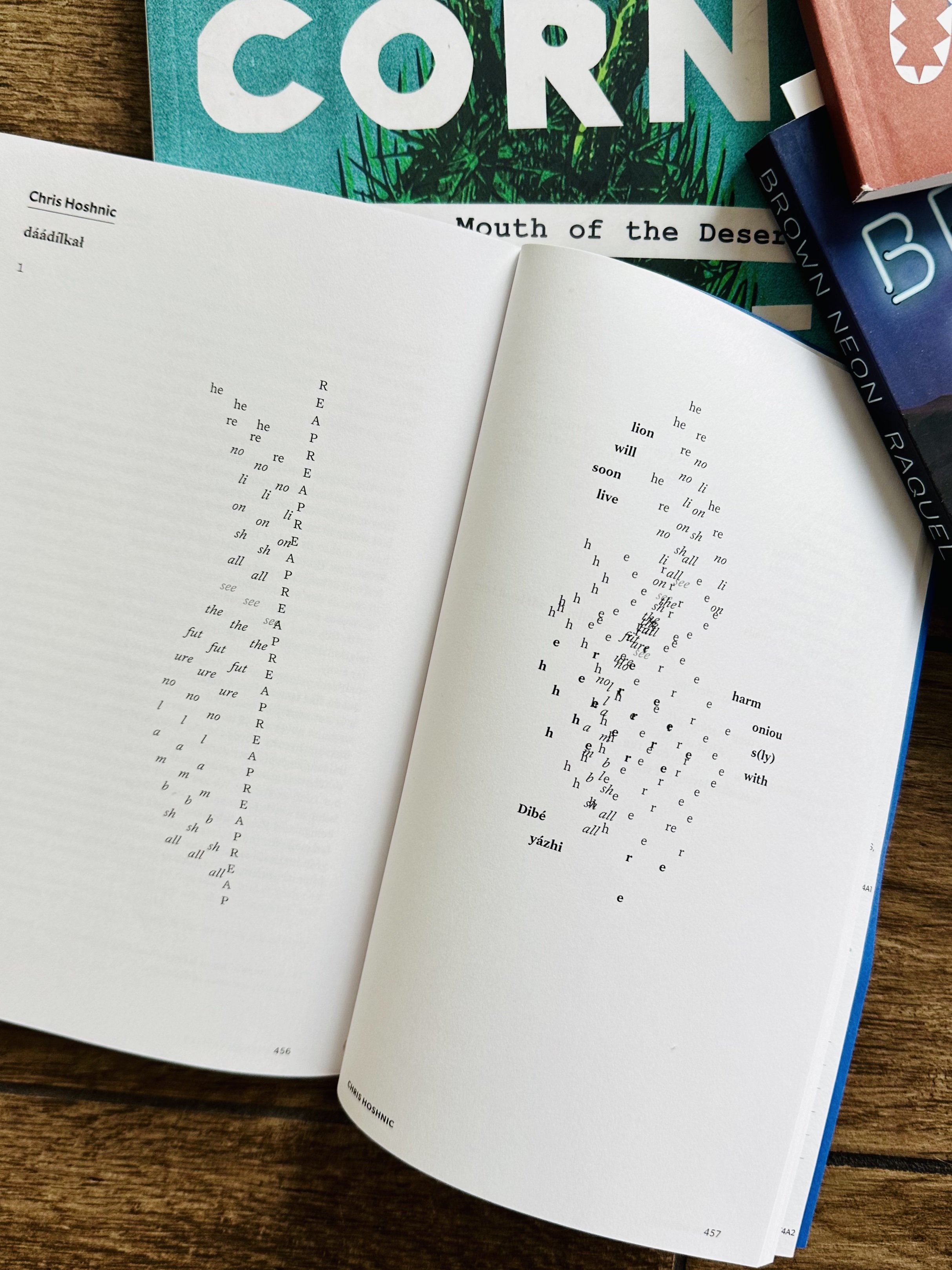

Chris Hoshnic (Diné) is a poet, playwright, and filmmaker whose work moves fluidly across genres, weaving together story, performance, and the lived experience of contemporary Navajo identity. Honored with the 2023 Indigenous Poets Prize from Hayden’s Ferry Review and the 2025 Poetry Northwest James Welch Prize, Hoshnic continues to distinguish himself as a bold and innovative voice in Indigenous literature. His fellowships include the Native American Media Alliance’s Writers Seminar, UC-Berkeley’s Arts Research Center, and the Diné Artisan and Authors Capacity Building Institute, with support from Indigenous Nations Poets, Playwrights Realm, Tin House, and others.

Hoshnic now steps into a new creative chapter as the Editor in Chief, succeeding Claire Wilcox, a transition that marks an exciting moment for the publication’s continued commitment to Indigenous storytelling and emerging voices.

In this conversation, we wanted to discuss his participation in the Playwright’s Realm’s Native American Artist Lab, a groundbreaking program that IAIA students and writers should know about as they shape their own creative futures.

Chris Hoshnic, welcome to the StoryCorner!

Hello!

We thought it would be a good idea in this space to discuss your participation in the Playwright’s Realm’s Native American Artist Lab because it is such a novel program that IAIA students should be aware of as part of their writing career. But before we get to that, could you tell us about yourself and your writer's journey?

How did you get into poetry?

I participated in a program called Thousand Languages Project, which translates poetry and short stories from Hayden's Ferry Review. It is volunteer-based and those who tackle it translate work from the HFR archives into whatever language they want. When I started, the database had no Indigenous languages.

Given that the university sits on Indigenous lands, it was crazy to think that no Indigenous person had tried to do any form of translation for them.

And so my translation of my own poem, “Land is a Body is a Religion,” and another poem by Wendy Thompson, are the first in the archives. It’s not perfect, but hopefully, it'll open a lot of doors. When I think about translation, I don't think about how I can turn a word into another language. I think about the space between translations and what gets lost between.

I always refer to Solmaz Sharif's poem “Look” as a reference for translation when she says “It matters what you call a thing.” That small line in that poem tells you a lot about how much we are not giving language to certain experiences and certain things.

Sanaz Toossi, in her 2023 Pulitzer-winning play, English, says something to the effect that when we move from Farsi (or Mandarin or Navajo), and then move it to the English space, she says English is like rice, as in, it kind of just sinks. You can dress rice up, but nothing more. There's no poetry in that. At least not in the way that Farsi does, and I feel that way with Navajo, too. There are things that we have experienced in Navajo and through the community, through the language of Navajo, that we've yet to have a language for in English.

And so the translation process leaves a lot behind in that space. I like to explore that in poetry. I'm exploring that through film. And I'm exploring that through playwriting, too.

Fantastic, before we explore this idea more, where did you grow up?

I grew up on the Navajo Reservation in Sweetwater, Arizona. I like to say I grew up there, but for maybe the first three years of my life, I was hopping around with my parents between the border towns, around the reservations, and then in Phoenix. That's a time period that is very hazy for me. That's a memory that doesn't really exist. It feels less like a memory and it feels more like it exists in a movie somewhere, or in a song, or in a poem. I'm always envious of people who can remember things before the age of 4 and 5, because that's a whole new world you can tap into.

But I do remember I spoke Navajo at that early age. Navajo is my first language, and somewhere between 4 and 5, I lost a bit of that. And from that point on until I was an adult, I rejected Navajo as this othered language. I respected the English language through and through as the official language for most of my life until now.

Right now, with the Navajo language, I'm picking it back up. I'm, in a sense, relearning, but I'm also reconstructing the language, too. With this new understanding of it. I’m starting from a child's understanding of the language. I'm constantly saying to myself “this is word means so much more now than it did back then.” Words have much more contextual value. That's interesting for me, and poetry does this thing where you can dig deep, and like Natalie Diaz says, “pressure English” in a way that Navajo can do so easily.

It's so interesting to find ways to do that on the page. And Esther Belin, who's a mentor at IAIA, was actually one of the ones who said to me that Diné Poetics is a place to explore these things on the page.

I didn't know I was already doing that before I met her, and then I showed her just standard poems in my first semester with her, and she said to me in her kind way, “You can do a little bit better than this. You can push language.”

And she was right. The work I presented with no restraint was then featured in POETRY magazine.

Congratulations on getting into POETRY magazine. That's a great feat. Going back to what we discussed earlier, when you say that you lost your language, what does that mean?

It is this idea I've been ruminating on, of memory and nostalgia. It's a thing that I've been pressuring onto my play that I've been working on with The Playwrights Realm through the Native American Artist Lab. What is the idea of memory versus nostalgia? It comes from another poet, but I don't remember who exactly, that nostalgia was America's creation of what a memory should look like.

An example of this would be Reaganism. And what did America look like during that era of Reagan's administration?

This adoption of America and the American Dream was the thing to strive for. But it's also this thing that not a lot of people had, especially with BIPOC and LGBTQ communities, because they will never get to experience the American Dream. After all, it's so tailored to one specific kind of person.

And so when you grow up, and you think of yourself as a young child, especially for me in the nineties, I'm thinking that they always say it was such a good time, but that is such a nostalgic way of looking at something that it's so singular.

When you think about nostalgia, and you say we had a better existence in X time, that devalues everything else that has happened during the time of X, right? Like civil rights movements, war, famine, etc.

It kind of puts this pressure on this idea that you will never experience a certain kind of nostalgia.

I think Jake Skeets highlights this in his work, especially in his essay in The Memory Field. Memories are facts, and nostalgia is a feeling, and the funny thing is, the other side will always argue that we poets and writers are always about our feelings, but we work from a place of memory. We're always pulling facts first, and then we're tethering to those facts. We start with universal themes to dig into and pressure those experiences of memory.

And so when I think about a time when I lost my language, I have to dig into a time where the language existed before me, without me, and then with me.

That's how I think about my language and when I lost it.

When did you start writing?

This actually connects to that whole nostalgia and memory idea because I was so sucked into pop culture and sucked into media and television when I was growing up. You probably remember a time before streaming, when episodes or TV shows would come out weekly instead of all at once. And so there's never that feeling of I need to consume everything this weekend. Otherwise, I'm left behind, right? There's always that feeling of what's going to happen next week. There's always that cliffhanger. And so there were TV shows that I would watch.

I would take these TV shows, when some twenty-two episodes or so would end, and I would be left with a period of three months to sit with what is to come next. So I would use that time to write screenplays on construction paper and start writing them the next season.

So let's move on to The Playwright's Realm and the Native American Artist Lab. How did you hear about it? And what was the application process like?

I have a few playwrights and filmmaking friends, and we do this thing where we send each other opportunities whenever we see them. And so we'll be texting each other or emailing each other. I have a really good theater friend who lives in Minnesota, and I believe she was the one who sent it to me.

It seems so separate from the world of poetry and the world of film. And I understand that there's some relatability there. Theater and film are almost like cousins, but with playwriting, it felt even scarier because in the world of theater, the playwright is respected. But in the world of film, the screenwriter is a “nobody.” In playwriting, everyone in the production has to honor the language of the playwright's writing; otherwise, the play fails. And that's why I was kind of a little iffy about it. It felt like a lot of responsibility.

However, I took an idea from a TV pilot I had written years ago. It was 30 pages long or so, and I was not completely in love with it. And so I had two weeks until the deadline for the Native American Artists Lab. I thought, what can I salvage from this TV pilot to make it a theatrical experience? I rewrote the draft probably six or seven times within those two weeks.

In the worst-case scenario, I don't get it. Best case scenario, I do get it—after all, this is a development program. So they're going to help me develop it and help me turn it into what I want it to become. And so that was kind of the mindset that I had.

I think it is important to have friends and people in the community who understand you as a writer, but also understand you as a person. To have those people alongside you, and say, “Hey, I may not be right for this, but you could be,” is how community works.

So tell me about the play.

It’s about a young Navajo man coming back home to his grandmother on the reservation, and he is to translate the final sign-off, or “sign here,” on the transfer of a home-site lease over to another entity, as she is getting older and can’t take care of herself. She only speaks Navajo, and documents tend to have a lot of legal language in them.

Navajo was never written, and it should not be written to begin with. And, so to say, “sign here,” the translation would really be “to draw,” but if you want a direct translation, “put this object (pen) in front of this other object (paper)” or “place it before you.” There is a kind of movement in that which English can’t seem to grasp.

That was the obstacle of this play: how do you translate not only the language on the page, but yourself, your homeland, your culture, etc? And what gets lost in that translation?

There's so much context you have to bring into translating for something as simple as “sign here.” As to why you want to “place something before another” means something in Navajo. It’s visual, visceral, it’s movement, it’s sound. And so that's the protagonist’s journey; he's trying to translate throughout the entire play. It's just him and her, and they're in the space where meaning is always moving.

The law is difficult enough to translate into ordinary English.

Yes, a lot of legal language can't be translated properly to illustrate what exactly we mean in English because Navajo is not a legal language. My poem, “Land is a Body as a Religion,” is about legalese. That poem tackles it in a way that says, “you know all the legal language, says this, but my body and my community say that,” and so that's what the play is an extension of.

There are two Supreme Court cases on water rights on the Navajo Nation and if you go back to the last Supreme Court case, which the United States won and you read the entire document, they emphasize this concept of time in every other line. It's almost like poetry.

Every judge wrote in their verdict, “the language at this time does not indicate that we owe you water at any time,” and they reiterate the words “language” and “time” constantly, like poetry.

We interviewed Layli Long Soldier and that was interesting because of her use of legal documents and language. And how she realized that the use of Lakota within her poems, which were largely in English, made her Indigenous language lonely.

Yes, I haven't had a chance to read her interview, but I agree with her.

For me, specifically, it really is this thing that Raquel Gútierrez says about infrastructuralism. As writers, we're always either operating under a planned violence or we're always consistently asking for permission for violence.

So when you're operating under a planned violence as a fiction writer or poet, you're always writing under some kind of oppression, right? And so, the Indian, or in this case, the BIPOC person, never gets to be fully realized or fully themselves, because they're operating under a system of oppression. Whether that is Section 8 Housing, the reservation, food stamps, whatever that story is, the politics of that world are based on oppression.

But on the other end, we're also always asking for permission. An example of this is “LandBack.” We're asking for permission to own something, and it operates under the assumption that there has to always be some kind of power at play. Either we don't have it or we do.

The way that I see Layli's perspective on it is that we need to start operating outside of this idea of power, and let the language flourish on itself on the page. It being surrounded by English is a planned violence, but it is also asking to be present to the reader. Most readers often glaze over “foreign” words on the page; they don’t give them time or breath. That’s sad and as Layli says, lonely.

Yes, I agree. I feel the same when I incorporate Spanish into a poem written in English.

Can tell me about your experience in the Playwrights Realm program? You take your play to New York City. How did that happen? Paint a picture.

I started in October 2025, by meeting my mentors. Each mentor had a very unique perspective on my play.

Every month, I had a meeting with them with a brand new draft, and we hashed it out for two to three hours. Then I would go back and rewrite it again. I also had another mentor, who worked alongside me on my career as a playwright, asking, “What kinds of obstacles will I be facing? How can I produce this play in the future once this program's over? And where do I go after my first play?”

There's that connotation that your first display of a project is always showcasing your voice. But your second project is what you can do as an artist. And so that's how I was looking at this. I was trying to find my voice in playwriting.

As it got closer to New York in March of 2026, I chose my director and helped cast my play. This was the most grueling part because I was coming to the realization that these people are going to embody my words. That's where it starts to get surreal.

For the most part, your days in NYC are 6 to 8 hours of rehearsals, and there’s a lot of collaboration.

I remember sitting alongside my director, writing on sticky notes to them if something felt off. I remember I rewrote whole scenes mid-rehearsal. I had the stage manager run downstairs across the street, print out new pages, come back, and she would give the cast new pages.

I did that three or four times throughout the entire process. I also went back to the hotel at night and rewrote the entire script, and I would email it in at 2 a.m. I would come back the next day, and everybody would have the new draft. I did that three or four times, too. So you're constantly rewriting.

That’s such a wonderful opportunity. You are workshopping your play to make it the best it can be.

Oh, yes, there were cases where I wrote dialogue late at night—two days ago or 3 months ago—and when I heard it for the first time, I would cut and replace it, or just cut it all together. Often in rehearsals, we'll go back to the top, and we'll read it through again with that extraction.

In some instances, we’d cut something, and then two pages or ten pages later, I’d tap my director and I tell them, “Actually, we're not cutting that because that's relevant to these ten pages that come later.”

The director then tells the actors, and so the process goes in that fashion until we land a good story.

And what did you learn from the process?

I think I learned that playwriting isn't scary. I actually love it. The amount of control you have is so liberating because the only other place I truly had that was in poetry.

That's something that playwriting offers, that I think that something like screenwriting doesn't really get to do.

In poetry and in playwriting, you can play with language, and you can test it and see how far you can take it without anybody saying that's not working, or that just doesn't make any sense. Everybody in the Playwright's Realm is in support of your vision as the writer.

If you feel like you need a sixty to seventy page reprint in the middle of the night, they'd do it for you. That liberating feeling disciplined me as a writer, because I started thinking in terms of how I am in service of the story, and that freedom made me accountable.

Nice. So what is your advice to others? In terms of the program and your experience. Who do you think should apply for this program?

I think for every grant application is to really hone in on a narrative. And when I say narrative, what I'm really talking about is what is the story in your application that's going to win them over, because for me it's always been about the Navajo language, and it's always been about my relationship to it.

If you find your interest and you find your passion in, even if it's as simple as a comma—I hear poets sexualizing the comma, which is really interesting—what is the comma really? Who is it really serving? And so these are kinds of questions that you ask yourself as a writer and as an artist, and then you start to explore that, and you trend it. You put that on the page. You place tension on these Western views. It gets personal and political in the process. You put all of that in the application. And then you start to realize you're getting more opportunities coming in because your interest is enticing a lot of people in a new way.

That's great. Chris, thank you so much for sharing, and I can’t wait to see your play on Broadway or the West End.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a poetry book inspired by a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He participated in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a second-year fiction writing MFA student at the Institute of American Indian Arts. His poetry is published in Huizache. His other interviews and book reviews can be found at La Bloga, Chapter House's Storyteller’s Corner, Full Stop, Pleiades Magazine, and the Los Angeles Review. He is a graduate of Cornell, Princeton, and U.C. Berkeley Law School.