Book Review of “Somos Xicanas,” edited by Luz Schweig and published by Riot of Roses by Rey M. Rodríguez

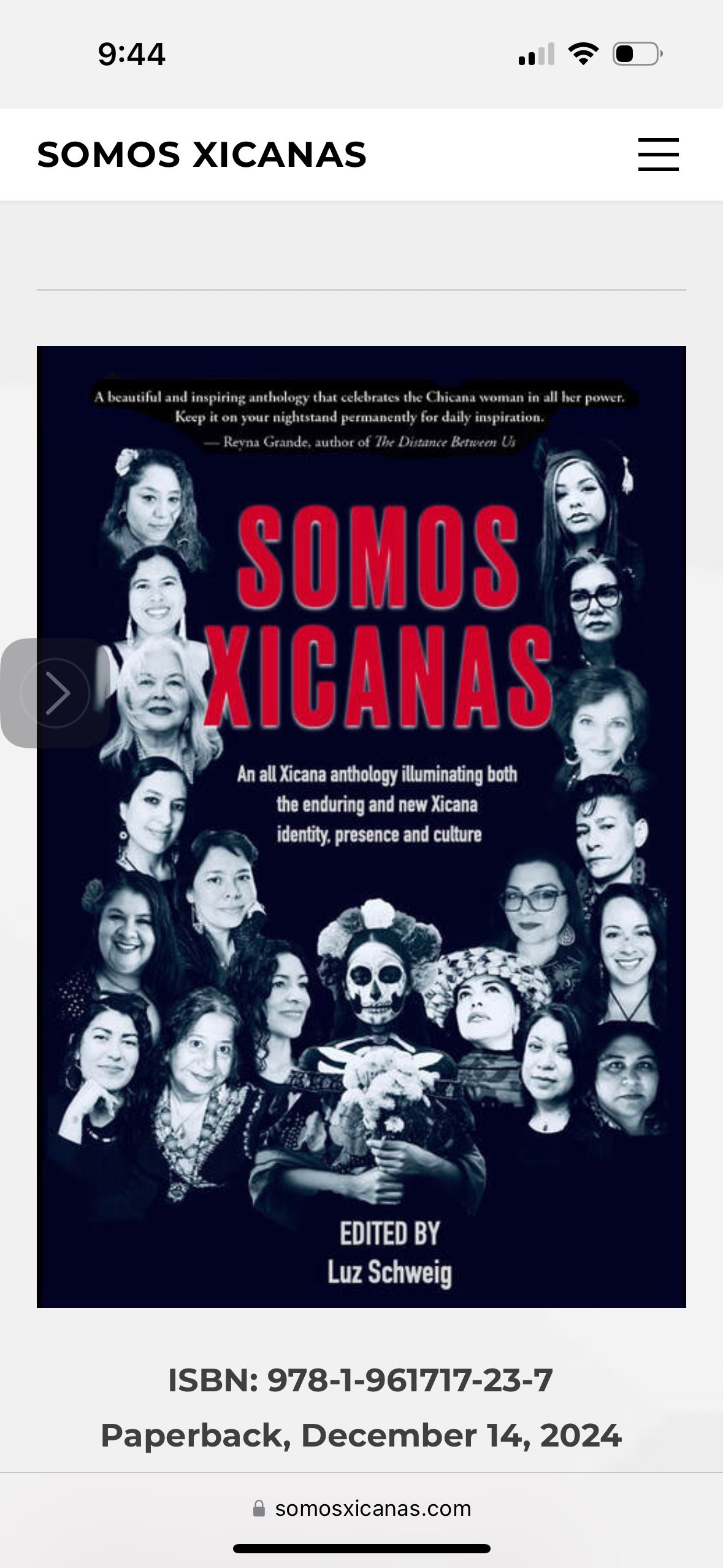

Somos Xicanas

Edited by Luz Schweig

Published by Riots of Roses (2025)

By Rey M. Rodríguez

In her essay, “La herencia Coatlicue/ The Coatlicue State,” Gloria Anzaldúa, the great feminist, queer Xicana writer, essayist, and poet, writes, “There is another quality to the mirror and that is the act of seeing. Seeing and being seen.” The new extraordinary anthology, Somos Xicanas, edited by Luz Schweig and published by Riot of Roses Publishing House, serves as such a mirror regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, or religion. It is a book that we all must read and reflect upon to see ourselves and to better see each other.

This groundbreaking book raises the voices of 80 Xicanas, including Xicana trailblazers like Ana Castillo, Sandra Cisneros, Lorna Dee Cervantes, Irene I. Blea, Carmen Tafolla, and the 24th poet laureate of the United States, Ada Limón. Other contributors include poet laureates Melinda Palacio, ire'ne lara silva and Angie Trudell Vasquez, along with the first Queer/Muxer Chair of el Partido Nacional La Raza Unida, La Doctora Chola, Vanessa Marie Bustamante.

Luz Schweig works as a volunteer staff member at Somos en Escrito Literary Foundation and is the creator of the Raza Story of the Year Contest. She grew up in Mexico City. Ms. Schweig also ran an international women's poetry journal for ten years, through which she edited and published five anthologies and a posthumous poetry collection. Schweig writes, “I have no doubt that if someone had introduced my teenage self to a book written by a Chicana it would have made a world of difference to me.” The book is medicine for many people.

At a time when we need to understand each other more, Somos Xicanas delivers vital messages about race, culture, class, economy, sexuality, and spirituality. The power and beauty of this triumph of literature is that it questions mainstream narratives and definitions of Xicanidad and shows what the term means through the writings of Xicanas instead of defining what this term means in stiff academic terms. There is no colonial filter or whitewashing done of who they are. The reader learns from the source in all of its complexity, grace, power, and beauty.

Daniel Chacón argues that there are two reasons why people have purpose: It is to endure and to flourish. This book is a perfect example of how we endure because it discusses our past pain, grief, joy, and beauty. And then, it also speaks to our flourishing in the actual poetry of each of the pieces. The organization of the book also expresses these mutually uplifting attributes. It is divided into three sections: Somos Seeds, Somos Stems and Leaves, and Somos Flowers and Fruits.

I have chosen one writer from each section to explore seeing ourselves and seeing each other. Xánath Caraza an inspiring, very prolific writer, and she writes in three languages: Spanish, English, and Nahuatl. Her poem “Serpiente de primavera/Serpent of Spring/ Koatl Xochitlipoal” was also recently published in her book, Corazon de Agua, published early in 2024 with Somos en Escrito. Caraza makes an important statement of language sovereignty by writing her poem in three languages. By doing so, she ensures that Nahuatl is reclaimed as an important and relevant language and not lost to the past. Her poetry also serves as an important bridge across time, languages, and cultures. It makes sense that it appears early in the anthology because of the theme of the seeds. The poem talks about how small things grow into things bigger than one could ever imagine. It also serves as a metaphor for what is to come from the Chicana voices in the book and in the future. The Spanish and English versions of the poem are remnants of a colonial past, and their juxtaposition to the Nahautl reminds us that there is so much we need to learn about the past before colonization, the present where the world is getting smaller and we need to learn more than one language to understand each other, and how we learn something new with regard to what the author wants to communicate to the reader depending on the language we read the poem in.

As in all of the sections, it is difficult to choose from the essays, poems, and short stories, but the one that struck me was the prose poem, “And now I am crying” by Jesenia Chavez. Chavez is an 18-year veteran public school teacher and obtained her MFA from the University of California Riverside. One of the through lines of the book is the lack of safety that women feel, and especially Xicanas, and this poem captures the complexity surrounding this issue. She writes, “. . . , and now I am crying in the car because I don’t always feel safe, and when I said it out loud I got sad, sad that I don’t feel safe in this body, in this city, in this planet sometimes.” But she doesn’t always feel this way, sometimes she does feel safe in her body, “. . . it protects me, it holds me, it remembers to be gentle even if I forget, it tells e things, but I don’t always listen.” Her armor inside of her brown female body is hoop earrings, zarape hats, and hablando en Español. It is also what her mother told her about what it took to be born. Her “Mexican Mami” with all of her 4’9” grace and power had her at Martin Luther King, Jr., Hospital and showed her what love is. So despite all of the weight of just being her, she “will not be erased” and she will not be devoured.”

Despite so many great poets included in this last section, I had to pick “Coyolxauqui” and “Coyolxauqui II” by Claudia Melendez Salinas. According to Mexica mythology, Coyolxauhqui, whose name in Nahuatl means "the one adorned with bells," was the daughter of Coatlicue, "the one with the serpent skirt," the goddess of the earth and fertility, and the sister of Huitzilopochtli, "the left-handed or southern hummingbird," the god of war and main deity who would lead the Mexica people to Tenochtitlan, the promised land. After a brutal battle between brother and sister, Coyolxauhqui’s body is severed into many parts by Huitzilopochtli, but ultimately, she becomes the moon. Melendez Salina’s first poem is only two lines: “Even when you’re fractured/ You are whole.” In the second poem, the poet appropriately brings Coyolxauqui to the present and describes the pain and suffering that the la migra, the IRS, Department of Corrections, Fentanyl and meth may have on the community. She then ends by writing:

Guerrera entera

encrucijada

aligned with Orion

for the winter solstice

at the crossroads

of what is possible

axis mundi

por donde circulan

las fuerzas del universe

laughing at la migra y el IRS

Circling back to Gloria Anzaldúa, she ends her “La herencia Coatlicue/ The Coatlicue State” essay by writing, “. . . I am never alone. That which abides: my vigilance, my thousand sleepless serpent eyes blinking in the night, forever open. And I am not afraid.” Somos Xicanas confirms that Anzaldúa is not alone. She has all of the contributors of the book to prove it, and they will move her work forward at a time when we need it. More importantly, she can now close her eyes and sleep. There is no need to be afraid because of the fierceness, wisdom, boldness of thought, and conviction captured in Somos Xicanas. It is now time for us to read, listen, and reflect upon these profound and important voices and then act.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a poetry book inspired by a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He participated in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a first-year fiction creative writing student at the Institute of American Indian Arts' MFA Program. His poetry is published in Huizache. His other interviews and book reviews can be found at La Bloga, the world's longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Chapter House's Storyteller’s Corner, Full Stop, Pleiades Magazine, and the Los Angeles Review. He is a graduate of Cornell, Princeton, and UC Berkeley.