Breathe In, Exhale & Seeing with Clarity in “Carbonate of Copper”

Review by Rey M. Rodríguez

Roberto Tejada’s new book of poetry, Carbonate of Copper, explores the notion of limitations, such as borders, as he examines the Rio Grande Valley towns of Marfa, McAllen, and Brownsville, among others, through his writings. He does so by reminding us through his work to treat this moment as sacred. The book, in a sense, is a meditation as Audre Lorde writes, and as he quotes, “The ability to consciously draw one breath after another.”

He implores this practice of being present with his first poem, “Hangman.” The “hangman” ominously presides over the poem as its title, waiting for the person to hang as they cross over from life to the other world. Tejada writes, “I tell to perpetuate in gray/are the callous mobs that occupy/ the frangible hour of my crisscross/” The lines also echo the moment when a migrant crosses the border between the United States and Mexico. An imaginary line that governments enforce, and that often creates a defining moment for those who cross it. Everything changes for the person once the line is crossed.

Reading Tejada’s poetry reminds the reader to breathe between line breaks and with his extra spacing between certain words. In “Night Festival,” he writes, “To reach the night festivities I press against the celebrants/ an abbreviated symmetry with me at the lower end of the hill/ in a synthesis a corporation an exile of bodies in danger/”. Ending the line at “celebrants” signals the reader to take a breath before starting with the next line. He uses the spaces between “synthesis” and “a corporation” for a similar purpose. The reader then has to ponder why the poet wanted to emphasize “a corporation”. In this way, the practice of paying attention to each word causes the reader to “consciously draw one breath after another.” Ending in the word “danger” gives a certain weight to what is to happen.

And yet, Tejada is not wedded to the notion that each poem must have a conventional meaning or, for that matter, a beginning, middle, and end. The spacing helps to take stock in the moment and let the reader play and flow with how the words sound and how that sound then helps the reader recall a memory or think of their own life or poetry.

Pauline Oliveros, a composer, improviser, writer, and teacher, deeply influenced Tejada’s work. He even begins the book by quoting her, indicating how important her work impacted his: “To make sounds rather than what sounds to make.” Therefore, when reading his poetry, it is important to read it out loud and listen to the musicality of the words. The reader should not only attempt to discern the meaning of each word and its association with those that surround it, but also listen to the sound they make. Tejada’s poems are meant to be read over and over. Each time, gaining a different meaning of what the reader retains from the practice.

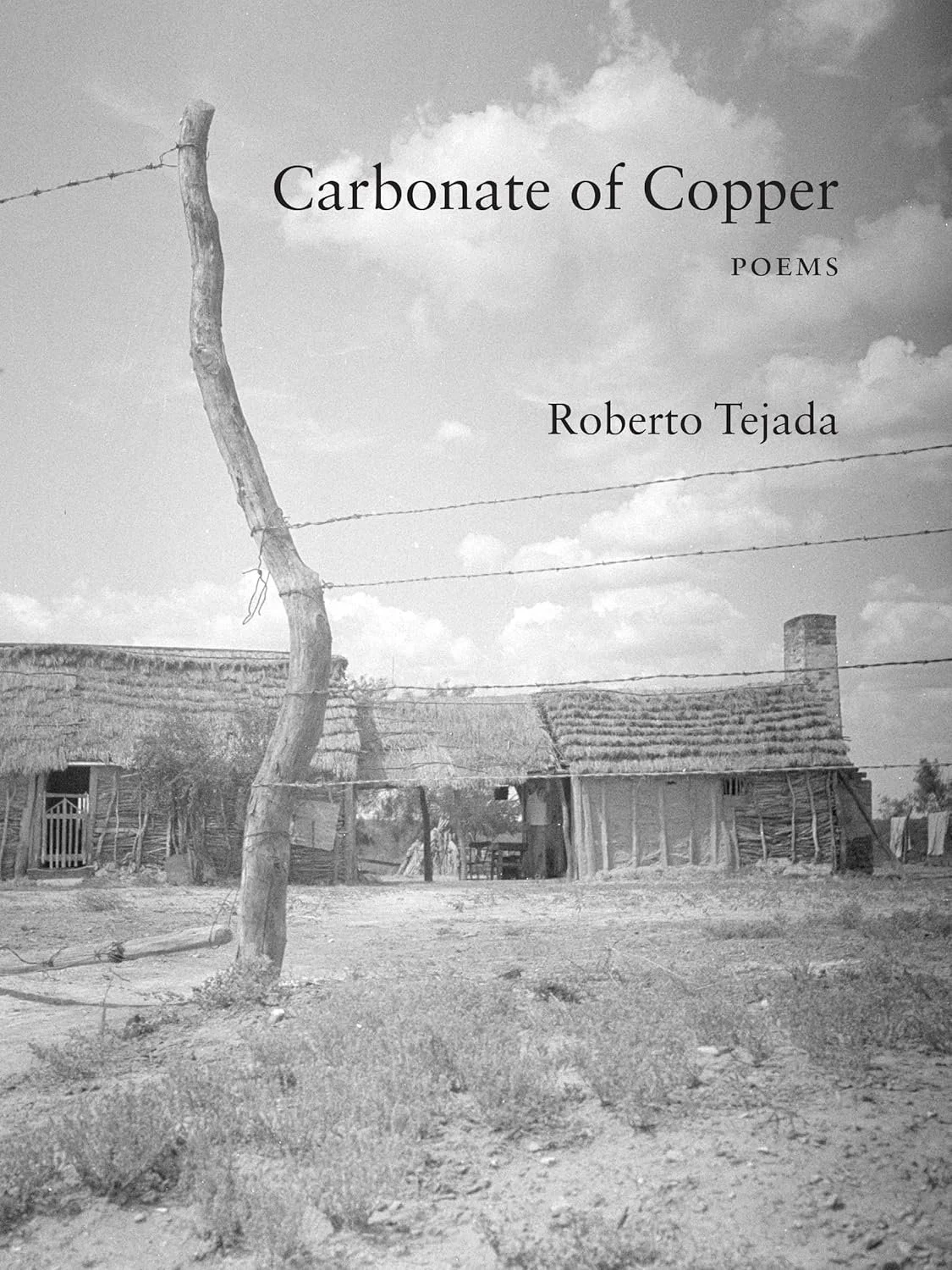

Further, Tejada’s work permits the reader to take stock of the importance of the moment without forgetting about the past. To emphasize this point, he created a visual essay with pictures he curated from the Farm Security Administration Photograph Collection available online at the Library of Congress, providing images of life in the Rio Grande Valley from 1939-1942. He makes the connection between the past of South Texas and the larger moment in which the country is living. The virtual essay “Sign for Bridge: a Fable” includes photos from Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, and Arthur Rothstein and invites the reader to create a speculative connection between worlds of the past and the present. Tejada writes in a Notes section of the book that he meant to create “a fable that telescopes between the historical past and the political imagination of our uniquely distressing present to which the images serve as testimony.”

What am I paying attention to as I take in that breath? Is it possible to think of my breath and all of the things around me simultaneously?

As I looked at the photos, I asked myself: What does this moment mean to me? How do I acknowledge and embrace it? What impact am I making in the world? What am I taking for granted? What am I paying attention to as I take in that breath? Is it possible to think of my breath and all of the things around me simultaneously? What other stories are there above and beyond those that have a beginning, middle, and end? How am I limiting myself to believe that poetry and, in a sense, my life are somehow constrained to a specific form or definition?

Reading Tejada’s poem promotes a practice for meditating on this moment. Seeing it clearly and realizing that change is needed. By doing so, we reflect upon and then deconstruct all of the limitations that we place on ourselves. We explode the idea that we are somehow helpless and constrained and begin to think about what role we can play in building a better and more just world.

“obtain as when there was food the field / abundant sun summer green / river valley chestnut little balm / border milestone” -from “Lyric of Breath”

The best example for me of this reflection on destroying constraints that we place on ourselves or others is Tejada’s “Carbonate of Copper.” In this poem and throughout the collection, the poet seeks a “lyric of breath.” In a sense, the reader must dispense of his narrow and constrained ideas of what a poem is and how it should function, and release into the idea that poetry is something much more expansive than simply the word on the page, but it also includes the sounds that are made when it is read. For example, in addition to understanding the words, “obtain as when there was food the field/ abundant sun summer green/ river valley chestnut little balm/ border milestone/” How does it sound in your mouth when read aloud? What do the words make you feel? Is it different than simply reading the words and trying to understand what they mean? What happens when the reader releases into the sounds of words? If I had not read Tejada’s work, I would have kept my narrow notions of what a poem should do for me and how I should read it. After reading his work and wrestling with it, I now have a much more expansive idea of the power of a poem to move the reader.

At a time, when empathy seems to be waning, Tejada’s words provide us with a path to find our way back to our humanity so that we remember and stand up for those marginalized by this hyper militarized regime that condones the kidnapping of innocent people off our streets, the removal of immigrant foster childrens from families, the mass detention and deportation of Brown and Black people, the destruction of our health care system for the poor, the erasure of history, the premeditated racial and ethnic cleansing of our country through a cruel immigration enforcement policy, and an attack on our nation’s most important academic, scientific, artist, democratic, and cultural institutions. I hope that after reading Carbonate of Copper, we will breathe in, exhale, and see with clarity the moment we are in. Then we must act individually and collectively to regain our sense of solidarity, reciprocity, joy, interconnectedness, and love to rebuild our notions of ourselves and our world.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a non-fiction history of a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He also participates in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a first-year fiction creative writing student at the Institute for American Indian Arts' MFA Program. This fall his poetry will be published in Huizache. His other book reviews are at La Bloga, the world's longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Charter House's blog, IAIA's journal, and Los Angeles Review.