Book Review of Matt Sedillo’s, “Mexican Style” by Rey M. Rodríguez

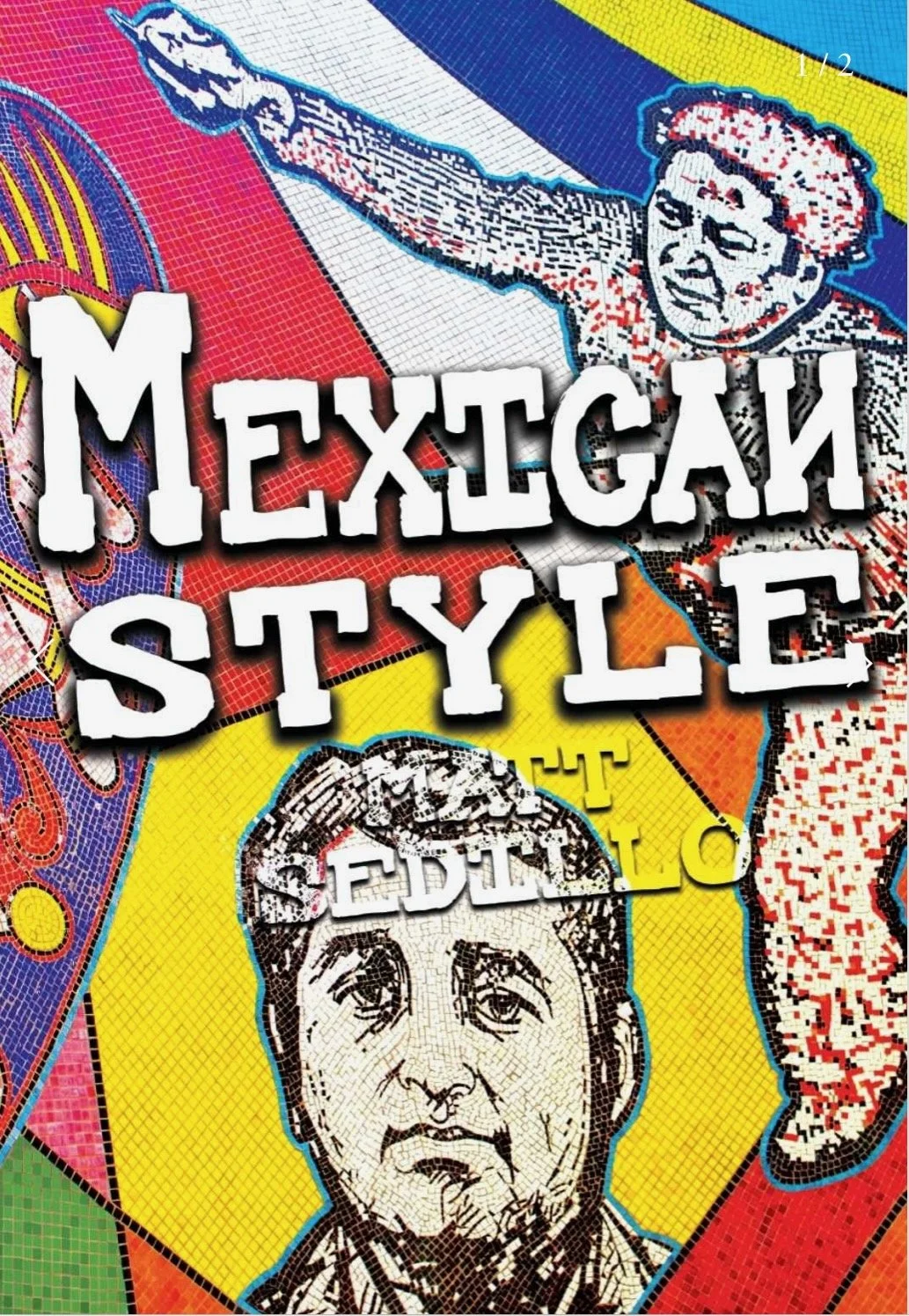

Mexican Style by Matt Sedillo and Published by FlowerSong Press ©2025

In his book, “from our land to our land,” Luis J. Rodríguez writes, “I also know this: I belong anywhere.” To arrive at this existential understanding of self he had to dismantle negative notions of how society viewed him and discover Chicano and Indigenous spirituality, history, and art that for too long had been partially erased, suppressed, and, only now, are becoming more accepted. For the youth of today, especially for those of color, that pilgrimage to belonging remains exceedingly difficult. Increasingly, they rely on new voices in poetry to explain the past and craft a different narrative as to who they are. One poet who is doing this remarkable work and someone who should be carefully studied is Matt Sedillo.

His third poetry book, entitled, “Mexican Style” coming out this March by FlowerSong Press, Sedillo opens the reader to a whole new expanse of history and art, setting the stage for those feeling marginalized to a profound sense of belonging. Based in Los Angeles, Sedillo is a Chicano poet, writer, creative director, and public intellectual. Recently, his poetry received international recognition when he read with Nobel Prize winner, Jon Fosse, during the Dante’s Laurel Awards at the tomb of Dante Alighieri in Ravena, Italy. Sedillo received the Dante Laurel the prior year. In Medellín, Colombia, this summer, the International Festival of Poetry invited him to read his poetry in conversation with over 80 other poets from over 40 countries.

This international recognition is new for Chicano poets. While the world is highlighting Chicano poetry the same is less true in the United States. Of course, we have Ada Limón, the US Poet Laureate, but one poet from a population of over 65 million Latinos, sixty percent of whom are Mexican American and many of those under the age of 20, certainly requires more. Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo, Luis J. Rodríguez, Vincent Cooper, Viva Padilla, Jose Hernandez Diaz, Octavio Quintanilla, Alejandro Jimenez, Eduardo Corral, Sonia Gonzalez, and others, represent a new and powerful counter-narrative to an often negative representation of Brown people in the mass media. Although rarely acknowledged on the national stage, each expresses important universal ideas as Chicana/o poets, during what feels like a Chicano Renaissance. Sedillo articulates the needs and desires of working-class Mexican Americans trying to survive a capitalist construct.

Sedillo’s work echoes back to poets like Langston Hughes, who almost 100 years ago, ignited the Harlem Renaissance with poems, such as “I, Too” when he wrote:

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes

But I laugh

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

Here, Hughes calls out his humanity amid a racist country that sees him as inhuman. Sedillo’s poetry also demands that society see Chicanos in our humanity. His writing reframes Chicano identity within modernity so that it is represented in all of its richness and complexity.

Sedillo’s first book of poetry, “Moving Leaves of Grass'' referenced Walt Whittman as Hughes did to Whittman’s poem, ‘I Hear America Singing' in which the 19th-century poet celebrates how each person contributes to the United States. Whitman, Hughes, and Sedillo converse across time about what belonging means in the US. Hughes and Sedillo remind Whitman that he must include Black and Brown folks.

In his poem, “El Martillo,” Sedillo writes in a more direct way than Hughes, but gets to the same point when he says;

Yo soy el martillo

The hammer

The builder of bridges

The destroyer of walls

And you shall greet me as a brother

Or you shall come to know me

By the hammer’s fall . . . .

In his poem, however, Sedillo is not waiting for tomorrow — he is demanding a just world now. He must unequivocally remind Whitman that Chicanos belong, because Whitman wrote, “What has miserable inefficient Mexico – with her superstition, her burlesque upon freedom, her actual tyranny by the few over the many – what has she to do with the great mission of peopling the new world with a noble race.” Sedillo also links Whitman with a certain Presidential candidate who recited almost identical sentiments 169 years later when he writes::

What has miserable inefficient

Mexico to do with peopling the new world

Walt Whitman

1846

When Mexico sends their people

They don’t send their best

They’re bringing their crime

They’re bringing drugs

They’re rapists

Donald Trump

2015

Sedillo ends his poem by saying:

The battle has been won

The decisive blow has been struck . . .

. . . I will build the bridge

I will destroy the wall

Yo soy el martillo

The hammer

Sedillo’s poetry shines brightest when he recites an almost hypnotic declaration of Chicano history, rarely mentioned or known in the broader US narrative. In his poem, “I, Chicano,” which references the great Chicano poem, “I, Joaquin” by Corky Gonzales, Sedillo writes:

. . . The fear of a Brown nation

On a bronze continent

The motive engine

Of the Mexican Question

The Chicano condition . . .

Later he continues:

May I carry the movement in my heart

Wear my heart on my sleeve

And enshrine our heroes

In these poems . . . .

He fulfills his promise by listing many of the heroes of the Chicano movement who without his poetry may be forgotten by generations of Chicanos and others who need and should know them to build a stronger democracy. People like Bert Corona, Rudy Acuña, Cesár Chávez, Dolores Huerta, Juán Gómez-Quiñones, Corky Gónzales, Reyes Tijerina, Cintli Rodríguez and many more mentioned in his poem deserve to be remembered and studied.

This knowledge is critical because it ensures that Chicanos are viewed on par with whiteness. If our history is erased or ignored, are we truly human? Do we belong to this democratic experiment?

Without the poetry of writers like Sedillo and others, Mexican American lives become expendable. In the 1930s, the U.S. government removed approximately one million Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans from the United States to Mexico. Repatriation occurred across many different states, with an estimated 75,000 people forced from Southern California. An estimated 60% of them were U.S. citizen minors due to birthright citizenship. Trump is calling for the same policy in 2024.

Sedillo describes another notable incident of violence in “The Assassinations of Rubén Salazár.” Salazár, a prominent LA Times investigative reporter, wrote on civil rights and police brutality. On August 29th, 1970, LA Sheriff Deputy Thomas Wilson fired a tear gas canister into the Silver Dollar Café after a Chicano Moratorium rally, killing Salazár. Many regard Salazár’s killing as an assassination since he was the most prominent Chicano voice at the time. Sedillo writes:

. . . A reporter

A war

A murder

A cover up

An investigation

A moratorium

A police riot

Hit pieces

Redactions

The Assassinations of Rubén Salazár.

If we are to obtain the sense of belonging that Luis J. Rodríguez achieved, then we must read Matt Sedillo’s poetry because of its relevance and it reminds us of a past that must not be repeated, but sadly seems to be.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a poetry book inspired by a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He also participates in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a first-year fiction creative writing student at the Institute of American Indian Arts' MFA Program. This fall, his poetry is published in Huizache. His other interviews and book reviews can be found at La Bloga, the world's longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Chapter House's Storyteller’s Blog, Pleiades Magazine, and the Los Angeles Review.