Book Review of Nobody’s Pilgrims written by Sergio Troncoso by Rey M. Rodríguez

At a time when a majority of the US electorate has elected a candidate who scapegoats the immigrant community for all of the country’s problems and threatens mass deportations, I find solace in reading Chicano writers who remind us of our better selves. One of the best at elevating us is Sergio Troncoso, a writer recently inducted into the Texas Literary Hall of Fame. He is the author of eight books, including, “A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant’s Son” and edited “Nepantla Familias: An Anthology of Mexican American Literature on Families in Between Worlds.” A Fulbright scholar and a graduate of both Harvard and Yale, Troncoso is past president of the Texas Institute of Letters and has taught at the Yale Writers’ Workshop since 2013.

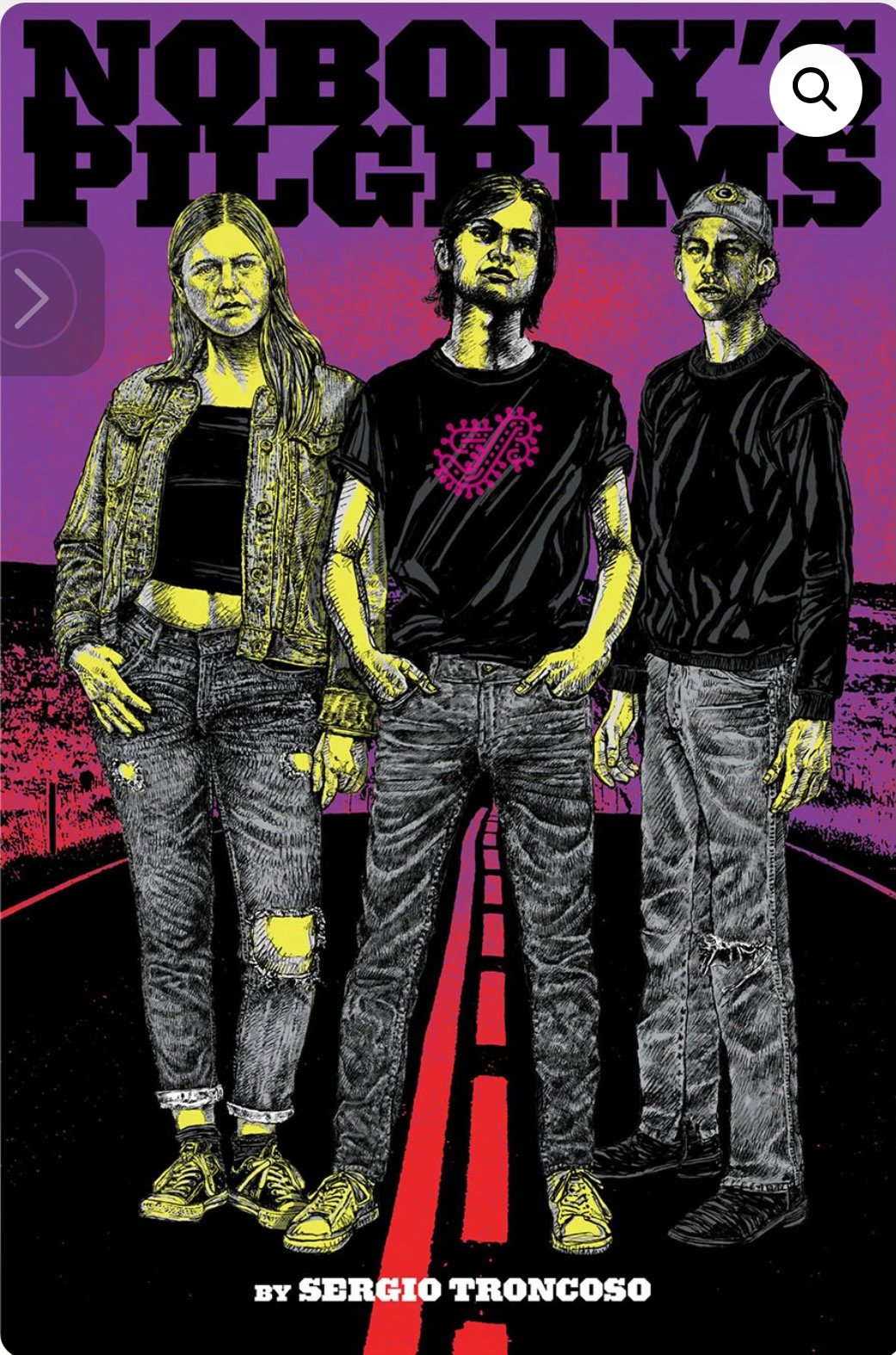

His most recent book, “Nobody’s Pilgrims,” is a masterfully wrought thriller road trip from El Paso, Texas to Kent, Connecticut. An orphan, Turi is a 17-year-old who lives in the back of his little house in Ysleta, a suburb of El Paso, and is simply trying to survive now that his parents are gone. Throughout the novel, he transforms from a young man who dreams of love as an abstraction to one who experiences it as a powerful connection between two people, even if the other person is seemingly from a completely different world from him. His first love is Miss Garcia, the high school librarian. She is older and, of course, unavailable to Turi, but she appreciates that he’s a reader. Instead of love she constantly feeds Turi books. This kindness helps him when he later serendipitously meets Molly in rural Missouri, during a dangerous road trip to Connecticut, a place Turi has only read about in a book that Miss Garcia gave him. He is on this journey trying to escape people who are trying to kill him for stealing a truck he got into in El Paso. At least that is why he thinks they want to do away with him and his friend, Arnulfo. In reality, it is for a very different reason. In any event, Turi connects with Molly, a poor white girl, in a way he has never felt before all the while trying to escape his killers.

And like all great thrillers, Nobody’s Pilgrims tells a riveting story but also addresses important everyday issues, such as racism. Not all along the way are welcoming to Turi and Arnulfo as they cross the country. Some are, but others are racist and xenophobic. They harbor notions that Mexican Americans are vermin or that Mexicans should not live in this country. The book explores how Turi and Arnulfo keep this racist poison from infecting their souls while facing the hate. Turi and Arnulfo fight for their place in the United States rather than assume they belong. Turi, in particular, knows he must survive here because he is never turning back. Connecticut is where he will make a home.

The story moves quickly from the first sentence to the last, but it’s also a study of Aristotelian philosophy, as the author often mentions in many interviews about the book. Troncoso, a doctoral student of philosophy at Yale, studies basic truths while telling an exciting story. As he has said many times, he is studying character and how it develops through action. He uses his characters to see how young people respond when they face evil. It’s an adventure novel about how people become who they are, through these first experiences.

But to me, the most interesting question I had after reading this fascinating book with many Easter eggs and thrilling plot twists was why the book is called, Nobody’s Pilgrims. In an interview that was later published in the literary journal Pleiades, Troncoso explained to me that many years ago he was asked to give the White Fund Lecture in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Judge Daniel Appleton White, a contemporary of Thoreau and Emerson, established the lecture and founded the Salem Lyceum. The first public libraries emerged from these lyceums in which people would donate books so that the public would have access to books and knowledge, especially those who didn’t have the income to go to schools like Harvard or Yale. Past speakers include such great writers as Junot Díaz, Ernest Hemingway, Julia Alvarez, and others. And for purposes of tying to the theme of immigration, Lawrence Massachusetts is no longer a majority-white community. The majority are Latino inhabitants from Central America, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic.

After reading White’s memoir, which was written in the mid-1800s, Troncoso learned that the immigration debate has not changed much. White complained in his book, among other things, about the rich Bay Staters and how they treated newly arriving immigrants. He reminded them that not long ago their English pilgrim ancestors were also immigrants. While some of these English pilgrims founded Plymouth Colony and Jamestown, others died of starvation or participated in cannibalism to survive the harshness of life in the New World. In the mid-1800s, the new immigrants came from England, Ireland, and Germany. Those New Englanders who were now settled and rich wanted to shut the door to these new immigrants. Troncoso realized that this story is simply repeating itself today.

In the end, Troncoso writes about the new pilgrims of this country. Those who some are calling vermin or saying that immigrants are poisoning the blood of this country. In other words, those people who some people would call nobody’s children. The reality is quite the opposite. These immigrants—like Turi, Molly, and Arnulfo—represent as Troncoso has confirmed in his writing and lectures the best values of this country. They show us what it means to work hard and make it on your own. They show us the importance of fighting for your place. They show us that we need each other and we must help others to succeed. Troncoso often says that these are the basic values that existed when this nation was founded. I would argue that they even existed before its founding. Indigenous people knew the importance of community and reciprocal action towards others to survive. It is the basic foundation of any civilization—the social contract. But too often we have forgotten these values of social cohesion and mutual respect.

In the end, Troncoso says and argues often in his talks and through literature that striving to be a good citizen and working to build a better world for yourself and others, instead of assuming your privileged place, is Aristotle's ideal through and through. The author is clear that Aristotle teaches the importance of work and the need to act to find meaning in the idea of the good. Threatening to deport hard-working immigrants who are only in this country striving to live out the American Dream will only weaken this country. Troncoso, through Nobody’s Pilgrims, reminds us that only practical, in-the-trenches Aristotelian understanding will be achieved through work and struggle, like new immigrants live out every day as they work in the fields, clean our homes, and do all the work that other Americans would never do. I hope this review convinces the reader to pick up Nobody’s Pilgrims for a great read and a reminder of what this country aspires to be.

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a non-fiction history of a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He also participates in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a first-year fiction creative writing student at the Institute for American Indian Arts' MFA Program. This fall his poetry will be published in Huizache. His other interviews and book reviews are at La Bloga, the world's longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Chapter House's Storteller’s Blog, IAIA's literary journal, Pleiades Magazine, and Los Angeles Review.