Book Review of "Sons of Salt" written by Yaccaira Salvatierra by Rey M. Rodríguez

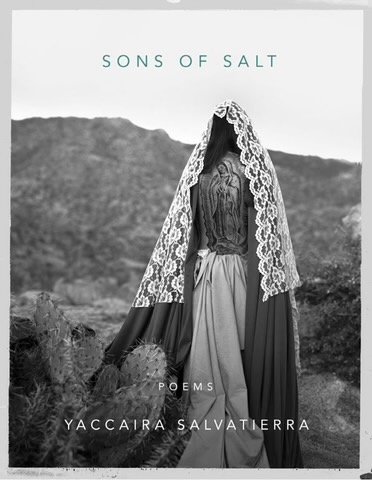

“Sons of Salt” by Yaccaira Salvatierra

by Rey M. Rodríguez

“Sons of Salt” by Yaccaira Salvatierra captures with extraordinary skill and tenderness the love, grief, joy, and ultimate peace that a Latina single mother holds for her two sons finding their way into manhood. As a mother and educator, Salvatierra is uniquely suited to tell this story, and she does it with grace and dignity, elevating to high art the universal story of raising boys to become men without a father present. For a debut poet, Salvatierra exhibits exquisite command over her craft, compelling the reader to read each poem closely until there are no more poems to read or pages to turn. I could not put this book down and even when I did I wanted to read it again, like a movie that has too many Easter eggs in it requiring the viewer to see it again and again to discover them all.

The first poem, entitled, “Prologue,” seduces the reader when she situates us on California’s Coast Highway 1 and writes:

“Hijo mío, the story goes like this: when the Ocean imagined you

It stretched a mighty wave, reached into my chest

& broke the strongest rib above my heart to build you—

I am exposed above the heart, left on the shore

unprotected. Seeing as I was, sparrows filled the emptiness

of me with a dome-like clay nest & laid their eggs.”

As a parent, this passage begins to describe the love that one feels for their children. So much goes through a mother’s mind when she holds her baby for the first time. The moment exposes her “above the heart” in a way that cannot be captured by words, but Salvatierra certainly comes close to doing so in this poem. A parent can only imagine their child’s future and hope that it all ends well because one never knows. Once a mother has given birth, an emptiness sometimes emerges that must be filled by those around her. I see the sparrows as all of us, including nature, not only participating in the raising of the child but also mending the mother so that she may carry the responsibility of motherhood. Salvatierra ends the poem by writing:

“Longing for your song, I called to the Ocean to send

a wave upon me: sea salt on a wound,

the sea swelling near my ear.”

There is great joy in being a parent, but it is not without its pain. The metaphor of “sea salt on a wound” reminds the reader that there can be a sting from loving so much and the sea swelling near her ear reminds me of how grief can feel like a wave rising to cover the mother’s head when things go terribly wrong.

Throughout the book, the reader never finds out what has gone wrong exactly, but a strong overtone of grief runs through much of the early poems. In the poem, “Protection” the main character walks on a shore with an elderly person and she is told that her purpose is to guide and safeguard all who hear her. She thinks of her brothers who are still protected and her sons who will eventually leave her side. On the next page in a four-line poem entitled, “What María Would Say to Self,” Salvatierra reveals in a footnote that one of the sons is lost to the streets of San Jose and the mother mentioned in the Prologue is looking desperately to find him. After discovering evidence of her son’s stuffed lion and a blue blanket with an image of Superman each being held by different, smokey silhouettes of other children walking the streets of downtown San Jose, she parks her car in front of the blue-gray Victorian cottage she lived in when her sons were young on N 11th St. She knocks on the door and shows pictures of her son to the tenants. She asks if her son’s shadow has come by for shelter. Salvatierra then writes, “When their heads shake from side to side, another bird inside of me buries its beak into its feathers—& silences its song.” The imagery powerfully echoes the pain and grief of not knowing where one’s son may be in the urban landscape.

The book, which is broken into eight separate sections, takes off from this loss and through a series of dream sequences that are appropriately used to explore a mother’s journey to find peace following loss. Inspired by the work of Layli Long Soldier and others, Salvatierra also employs forms, specifically the square, several times throughout her poems. The square could represent the body or simply a box that we put ourselves in when attempting to address problems. There is even a suggestion like in “Below the Horizon” to think outside of the square box as the words “the still Ocean” escape the confines of the form and spill out onto the page. Salvatierra masterfully uses this recurring shape to tell in many different ways and in turn enhance the reader’s understanding of the poetry and expand one’s notion of what the words can mean.

To explore various questions that Salvatierra has regarding what her character’s sons may be feeling she employs the cento, which is a literary work made up of quotations from other works. She entitles it, “An Off-The-Record Mexican/American Cento” and she asks questions such as “What Happened to You?”, “Would You Be Able To Escape To Another Room Without a Wound Unscathed”, and “Is There a Father You Want to Emulate Who Sings to Their Sons?”, among others. Salvatierra studies 21 Mexican American male poets and she constructs poems responding to the posed questions from their poetry. She identifies all of the poets in the Notes section and it is an extraordinary list of poets, especially for this Chicano writer who would have gained immensely from reading such a diverse group of authors in his youth. Her ability to create a poem from other poems shocks the imagination. For example, she uses a quote from a poet that is not referenced and writes to the prompt, “Is there a Father You Want to Emulate Who Sings to Their Sons?”, “Remember, father said, pain awakens us to all the things we hold dear and that’s why it hurts . . .”

Salvatierra explores pain, grief, joy, and wonderment in “Sons of Salt”, but she does it through her unique prism that I hope other readers will take the time to read and study. Ultimately she finds a way through her poetry to transform all of these emotions into a kind of peace. She learns that instead of trying to avoid these feelings they are all a fabric of what is to live and that the deeper we feel the more alive we are. Her last line in the book says it best, “The deeper I am pulled in, the more I am.”

Rey M. Rodríguez is a writer, advocate, and attorney. He lives in Pasadena, California. He is working on a novel set in Mexico City and a non-fiction history of a prominent nonprofit in East LA. He has attended the Yale Writers' Workshop multiple times and Palabras de Pueblo workshop once. He also participates in Story Studio's Novel in a Year Program. He is a first-year fiction creative writing student at the Institute for American Indian Arts' MFA Program. This fall his poetry will be published in Huizache. His other book reviews are at La Bloga, the world's longest-established Chicana-Chicano, Latina-Latino literary blog, Chapter House's Storyteller’s Blog, IAIA's journal, and Los Angeles Review.

Cover Art: “La Virgin, Gelatin Silver; Courtesy of Delilah Montoya