Journey of an Intern: Hashtag Poetry

It’s a strange space to occupy, that space that exists somewhere between student and professional. It’s a place between school and career. It’s kind of like limbo, especially when you add to that nameless existence a low-residency MFA program. Friends ask, “Why are you always busy? What are you even doing? But you’re just, like, at home right?” Yes, my classroom is just my bedroom. Yes, it is mostly independent. It made sense that I needed some direction. I needed a space to occupy. My classroom exists through a screen and that day-to-day, face-to-face interaction was what I was hungry for. It was through this hunger that I found my way to Port Townsend to spend a winter interning at Copper Canyon Press. I wanted a place to wake up and go to every day. I wanted to be surrounded by poetry. I wanted to learn what the world of poetry looked like outside of the classroom.

On the first day of the internship, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I had spent years bartending, waitressing, making coffee. I’ve learned the art of the service industry in Seattle, where the closest thing you get to a uniform is a matching tattoo with another barista. Perhaps the same apron. I had zero idea how to present myself in an office environment. I did my best to dress the part. I channeled Sherilyn Finn a la Audrey Horne in Twin Peaks. Pencil skirts and button-up blouses. I covered my tattoos. I found my “Most capable looking ensemble,” to quote Cher from Clueless when she’s aiming to pass her driver’s test.

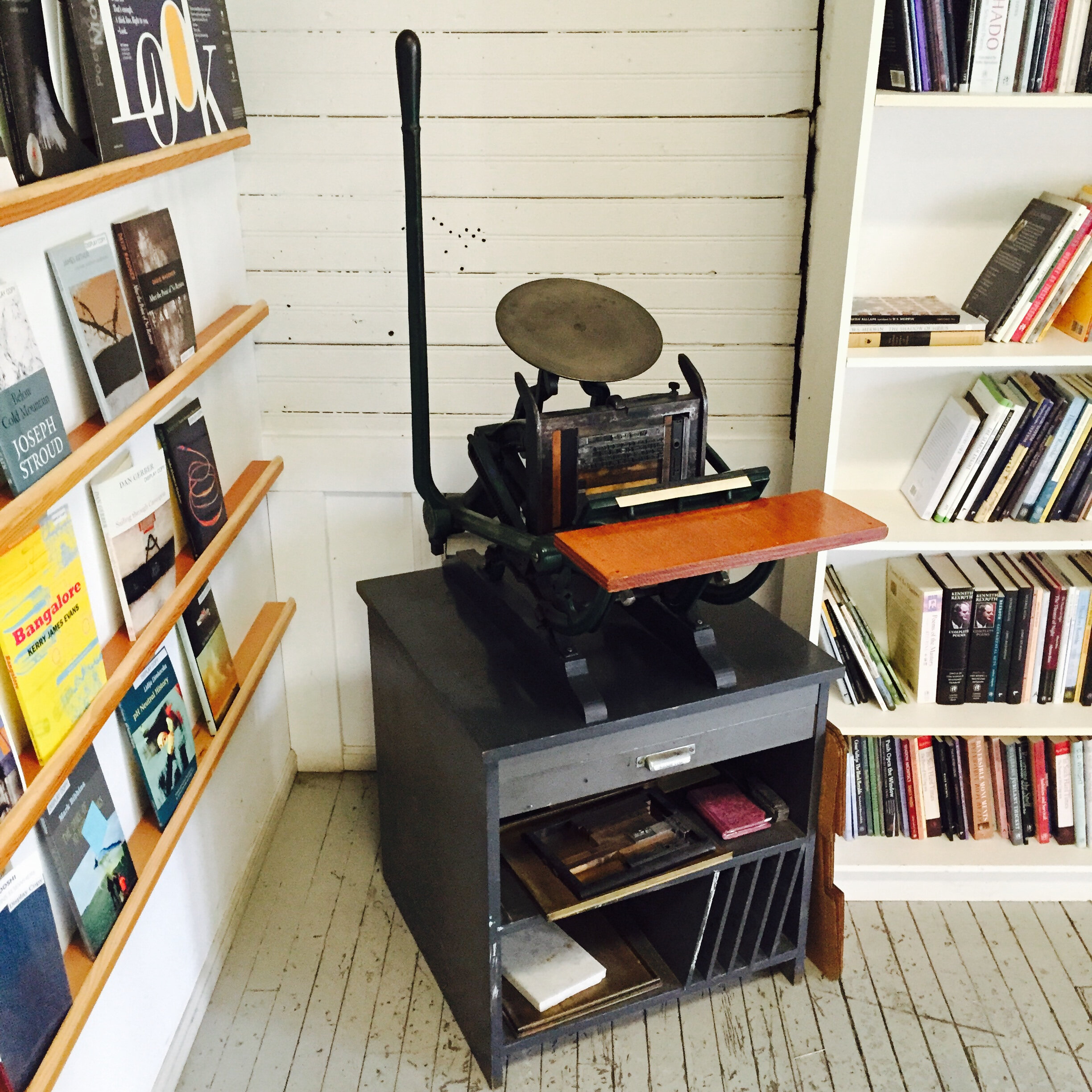

I walked in the grey rain along the beach to Fort Warden. It felt like the first day of school sans the lunch pail and free ride. When I walked into the old foundry building in Fort Warden, home to Copper Canyon since the seventies, my anxieties were alleviated. The building smelled old, not off-putting but familiar, and passing the wall of books that greeted me when I crossed the threshold was like walking into a crowd of people you love to see. Natalie Diaz, Michael and Matthew Dickman, Deborah Landau and Pablo Neruda.

I was warmly welcomed by my cohort of interns, a misfit bunch of ladies from across the country. There was a student from New Jersey, fluent in Russian and studying translation; a poet from Brown who wrote her thesis on Sylvia Plath. There was a nomadic, Western Washington grad who had traveled abroad before settling in Port Townsend to work at the esoteric book store, and a recently graduated fiction writer from Texas. Together we formed a literary melting pot in the Copper Canyon Press bullpen. Over the next five months we would share poetry, dinner parties, and even a bottle of wine at Bill Porter’s house while one of us housesat.

Over the first few weeks my professional cosplay was strong. Blazers and high-waisted skirts took over my closet and I became more comfortable with working reception, selling books, and reading five manuscripts a week. I was briefed on what my main focus for independent projects would be: Social Media. I was immediately amused, intrigued and a little bit relieved. I was going to learn how to professionally Instagram? The concept was strange but not completely foreign to me. I am, after all, the kind of girl who will prepare a kale smoothie, snap a photo of the kale smoothie, filter it, post it, and then consume it. It’s a strange, braggy, artistic outlet. Silly as it is, social media is a vehicle for communication. Advertising isn’t restricted to billboards and television anymore. It’s on our computer screens, on our phones, and in our personal Facebook feeds, Tumblr blogs and Instagram photos. Over the weeks that followed, I learned about branding: how to create content specific to the style and brand of Copper Canyon. I learned how to promote the internship program while applying that brand and style. I took photos around the office, everything from interns working diligently to a package of old Peeps on the head publisher’s desk. I documented life at Copper Canyon Press, made flyers and slideshows promoting the internship program. Hashtag Poetry. Hashtag CCP. Hashtag winter releases and hashtag intern lifestyle. Mostly, I felt lucky to be existing in a world of books. If we weren’t discussing poetry, we were reading it. We were learning about what it takes to bring a book into the world and it felt like alchemy. It felt magic.

One afternoon while standing at the copy machine I looked down to a pile of papers left by the recycling bin. Green Migraine, by Michael Dickman. The unpublished new manuscript lay unattended at my fingertips. During my lunch break I tore through it with the same enthusiasm one might imagine the creature Gollum having when he finally tears the ring of power from Frodo’s finger. I was stoked. At the end of the day I tidied up my desk and made the hour long drive to the ferry to spend the weekend in Seattle. The next morning I woke to discover the unpublished manuscript in my pile of personal papers shoved into my book bag. I immediately panicked. What kind of accidental poetry crime had I committed? I called the press right away. I explained my situation. My fellow intern laughed and assured me it was fine, as long as I didn’t attempt to sell it on the poetry black market or anything.

I rarely felt out of place at the Press. I showed up in the morning, made coffee, read poetry. Sometimes I answered the phones, sometimes I went right to work reading submissions. If I felt challenged, it was often in a good way. There was an incident with an Excel spreadsheet that sent me reeling into a nightmarish panic, but for the most part I was able to easily acclimate to the office environment. I was also challenged by a typical, slightly uncomfortable conversation while packaging copies of Frank Stanford’s book in the warehouse. An older volunteer was trying to make polite conversation. He asked about my MFA program and about my writing. When I told him I was writing a book about growing up on the Swinomish reservation, about abuse and alcoholism he seemed confused. “But how did you come to live there?” He asked, scratching his head while eyeing me up and down. Was he asking about reservations in general? And then I realized what he meant. Attending a tribal art college for four years had left me safely comfortable in my mixed heritage-ness. I’m not used to having to explain my identity as an indigenous person and also as a white person. I’m not used to having to explain that not all Native people look the same. Some of us have blue eyes. Some of us have black hair. Some of us are dark. Some of us are pale. When he realized I lived on the reservation because I was a reservation Indian he redirected his inquiry. “Your book is about abuse and alcoholism? Why is that? Why is it that it’s so prevalent on reservations? Why is it so prevalent in Indian communities? It’s sad, isn’t it?” I was silent. Yes, I thought. It’s sad. It was so sad that right at that moment I had to take my break and walk to the edge of the fort, to the water. I sat on an old bunker and looked out into the Port Townsend harbor and felt…sad. That night I went home to my little room and wrote a poem about sadness and felt some sort of relief, like it was medicine.

That’s the biggest gratitude I have for the internship, the poetry. Being immersed in it, inspired by it. We were given what I decided were “poetry rations,” our choice of two books a week. Each week I’d curl up with a little bit of whiskey, a book of poems and the moon. I’d sit in my room by the window, listen to the water and the wind and read. It felt like an important time, to spend the winter learning about poetry, while reading and writing it. I don’t cook so I spent most my evenings alone, poking at a pile of fish and chips at Siren’s, while tourists and elderly couples sat around me. But I always had the poetry.

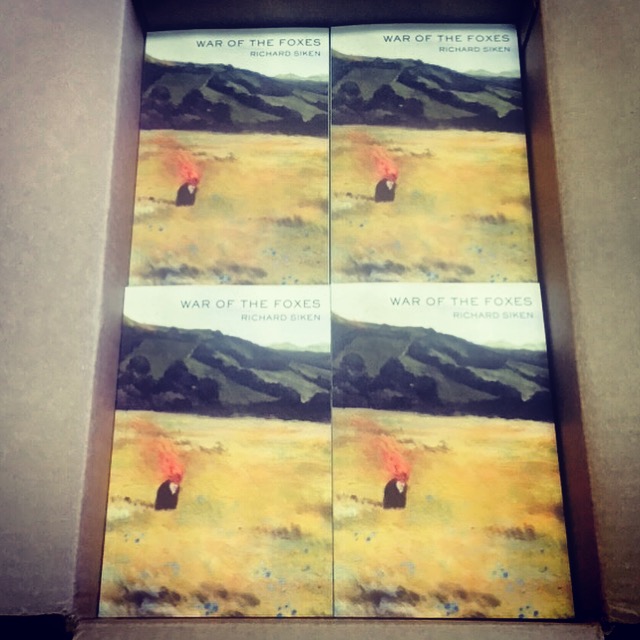

Each day the press revealed to me new details, little secrets about how the world of nonprofit poetry publishing works. One morning the interns and I huddled around the reception desk to watch the premier of a promo video we had helped work on. Maybe it was because we had single-handedly hung every one of the hundreds of postcards that whimsically fluttered from the tree in the background. Maybe it was because we could remember the very real emotion on the poet Richard Siken’s face as we quietly hovered in the distance while he spoke into the camera about poetry and how nonprofit publishing needs our help, but by the end of the two-minute promo video, all of us were quietly sobbing. It felt special, to be a part of something. To know that we somehow played a role in Richard Siken’s book, War of The Foxes, coming into the world. Whether we assisted on the video shoot, worked on the Tumblr blog, the Indiegogo crowdfunding page, or wrapped each book individually before shipping it out to the donors, each of us had done our part. When the book came in, it felt like such a celebration that we all joked about popping champagne. To watch War of The Foxes go from manuscript to book to special edition and into the hands of poetry lovers over the span of a winter was an intensely beautiful thing to see. That night we went to the only dive bar in picturesque Port Townsend, cheered over cheap pints of beer, and belted out karaoke into the night.

An image comes to mind when I think of the magic that is poetry, and the magic that Copper Canyon Press creates. It is a still from the promo video I assisted on. It’s an image of Richard’s hands as he writes on a piece of wood with a sharpie. In his handwriting are the words, “To supply the world with what?”