BRANDON HOBSON on The Unreliable Narrator

by Claire Wilcox

Drawings by Brandon Hobson

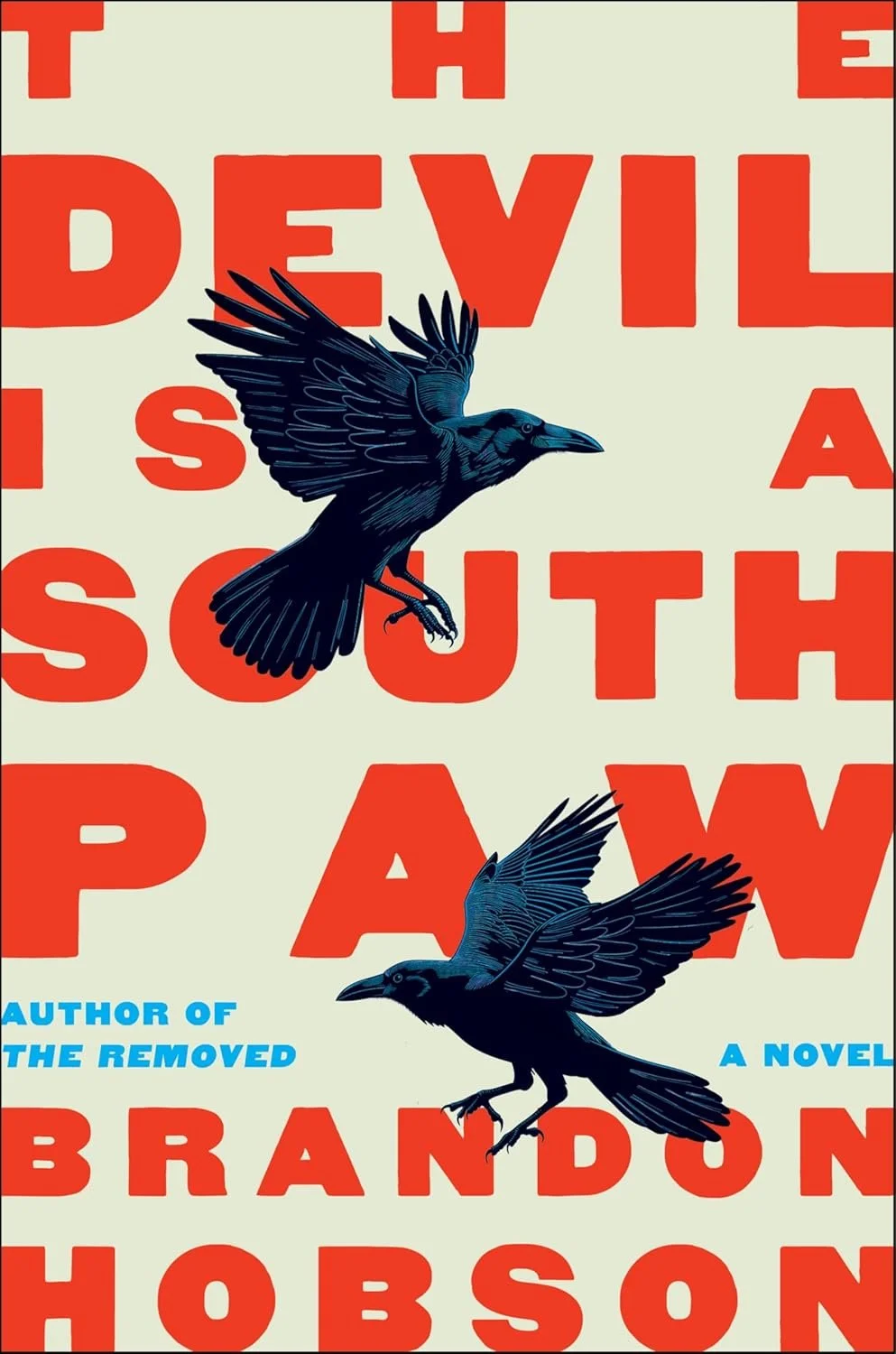

Hobson’s newest masterpiece, The Devil is a Southpaw, is a novel told by Milton Muleborn. Milton is a teenager incarcerated in a juvenile detention facility in Oklahoma. His manuscript comes with an additional bonus: it’s illustrated with Hobson’s own art, which is as haunting as his prose can be, at times.

Milton is envious, sometimes to the point of obsession, of another teen boy in the facility, Matthew Echota, who is a gifted artist and writer and who always charms the teachers. Matthew also later enjoys some wider creative success, to Milton’s occasional distress. Milton longs to experience a similar kind of recognition and acclaim for his writing. Milton tells their story with exaggeration, embellishment, humor and occasional references to the supernatural world. We can see that Milton, although underappreciated, is a very talented and creative individual too. At one point, Milton takes us, with his words, into a nightmare-dream like under-world where Matthew and Milton travel through low hanging branches and fog, come upon swamp flowers and donkeys, and receive guidance from Salvador Dali and Frieda Kalho. Their task, they are told, is to taste the salt, which they are lead to, and ultimately do.

Hobson is a master of blurring the line between the otherworldly and the reality we can perceive with our five senses. He is also a master of writing from the POV of an unreliable narrator. He builds tension by leading us into the mystery and then keeping us there, just on the edge of understanding, but never quite giving us all the answers. He writes about suffering, mental health, and pain, but weaves in just enough humor that the trauma doesn’t ever weigh you down so much that you want to stop reading. His characters are memorable and empathetic but often conflicted. All of his gifts with fiction shine here in his new book - if you loved his previous novels as much as I did, you’ll love this one too.

In this interview we discuss craft issues such as writing the unreliable narrator, structure, symbolism and revision. We also hear some of his advice for early- and mid-career writers. After reading a Hobson novel, it’s impossible to see the world in exactly the same way ever again. The Devil is a Southpaw is no exception.

How did you get into writing? Do you prefer writing for adult or children, and what are the challenges you've faced in both?

I started writing fiction in college after taking a creative writing course and an introduction to literature course. I wrote The Storyteller (Scholastic) for children, but I prefer writing for adults. I hope adults appreciate The Storyteller as well.

The Devil is a Southpaw:

I didn’t know that you were a visual artist as well as a writer. The images in your new novel are haunting and so perfectly matched with the text. In the process of writing The Devil is a Southpaw, in what ways did the text inform the art and vice versa?

When I started drafting this novel, I was interested in writing about a novel using art, my drawings and paintings in a story about suffering, particularly from envy, told partly through the lingering trauma of juvenile incarceration but also by using the art as a narrative device for Milton. In the novel I use acrostics, drawings, paintings, and an anagram (Sanbo Hornbond/Brandon Hobson). I knew I wanted to write this novel in an artful, challenging way. The drawings are supposed to show an unhinged aspect in Milton (e.g. his cryptic self-portraits 1988 and 2020 in Part 3) and hopefully reflect his anxiety and longing to be taken seriously as a writer and artist.

Milton is a mediocre, unappreciated writer, consumed by envy and pride. In the last pages of the book (spoiler alert) Milton says, “I have resigned myself to stay here, in asceticism, where I live day by day. To pass time I read and write unstutterably bad poetry, study the mystics and saints, and try to see the beauty in the natural world…here on this desolate land near the water, what else is there but hope?” I love these lines: words of wisdom, I think. What advice might you have for early- or mid-career writers who are actively pitching but not being snapped up by agents and publishers or whose work (so far) has been mediocre, at best? Is there such a thing as “mediocre” writing? What about for writers and artists with bouts of “obsessive envy”? What works or authors have generated that feeling of envy in you, and how do you cope with that feeling when you have it?

Writing takes time and a lot of work and revision. It's always best to find a community of honest readers, either in an MFA program or writing group, and exchange work with them. Look at great books and figure out how the writer is pulling it off. What makes the prose so beautiful? What is it about a certain phrase or sentence that makes us feel breathless. Poetry is good for this. I read my friend Sherwin Bitsui's poetry for the sheer beauty of the language. In terms of finding agents and editors, there's some luck involved, but there's also the problem many writers have, which is thinking too much about a general audience. Write the book you want to read, as Toni Morrison said. And be patient, get obsessed with your work and stay with it. My old teacher, the novelist Stewart O'nan once said, "The ones who make it are the ones who stick with it."

In the jacket of The Devil is a Southpaw it says the book is written in "the spirit of" Borges and Nabakov. Which stories or books of theirs have been most instrumental in informing your writing style and why?

I was thinking about a couple of Nabokov's books: Pale Fire and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. Nabokov was a master of the unreliable narrator, and I've always been a fan of his books. Borges' Ficciones is a fantastic collection that every writer should read. He really pushed the idea of what a story can be. His stories are often challenging and philosophical. Early on, they introduced me to structures I didn't know a writer could get away with; for example, he writes book reviews of books that don't exist, magical realism, those kinds of things.

There are so many recurring images and symbols in The Devil is a Southpaw that intrigue me, but that I don’t fully understand (e.g. shadows, illness, salt, lepers, even the title/movie/novel “The Devil is a Southpaw”). Any particular metaphorical puzzles or meanings you would be willing to name or reveal regarding these symbolic items (especially the salt!) in this interview?

I was thinking about salt as a symbol is for humility, as in the phrase "salt of the earth" referring to humble, good-natured people; and humility is the opposite of pride, which Milton suffers from, so eating the salt would be helpful for him because he recognizes later in life how destructive this pride is.

Craft:

You have the capacity to strike such a delicious balance between poles in your writing. Your books address deeply serious themes while also being wry and humorous. Your stories vacillate between whimsical surrealism and traumatic realism. Some of your characters are at once profoundly empathetic, and cringeily problematic, even violent at times. But in the end the reader still feels centered in the story unfolding before them and engaged in and connected to the characters. Does this balance just emerge from your writing naturally, or is it a product of deliberate revision?

Writing takes lots of revision in order to get it where it works best. Going back and adding details to help make connections, rewriting scenes and dialogue, cutting the fluff, those kinds of things. I'm honored you think so highly of my characters and themes I'm addressing. They come out of a desire to create and, in a sense, entertain myself. I like writing about serious issues that often begin with big questions, and stories are about problems and conflicts, otherwise they're boring. Trying to balance high stakes and conflict in a propulsive narrative is challenging in the best way. Writing can be work, but it's fun work.

You’re a master of the unreliable narrator. I love how Milton in The Devil is a Southpaw often talks in the first-person plural pronoun. I am guessing this is, in part, a way to show his unreliability, as if, by using this pronoun, he is trying to spread the blame. Are there any other reasons you chose to use that technique in his character development? What draws you to write from the POV of the unreliable narrator?

Part of writing in first-person already implies an unreliability (some may argue that all first-person narrators are unreliable to an extent), and fiction is about getting to the truth through a seductive voice. A first-person voice means seducing the reader in a way that's sort of manipulative in order to persuade them to continue reading. Milton tries to create an artificial construct that he can’t escape from by attempting to balance humor with sadness and manipulation to earn the reader’s sympathy. It's not easy, and it doesn't always work, but it can be fulfilling in the art of fiction.

Relatedly, and as a result, there are often mysteries left unsolved in your works. In The Devil is a Southpaw, we don’t really ever know the truth about Milton’s backstory. What exactly did he do to end up in juvenile detention and what is he confessing to having done? Similarly, in Where the Dead Sit Talking, we never really know if and exactly why or how Sequoya took Rosemary’s life. It’s the things not said that leave me wanting, as a reader, in a delicious sort of way. Reading your work reminds me a bit of watching a David Lynch movie. How do you decide what to obscure versus what to clarify in your novels? What are your reasons for writing in this way, into the questions rather than the answers, and how do you decide what you’ll leave as questions?

Those are the hard questions to think about as a writer. I've always thought what's not stated directly is often the most interesting, like what often happens in J.D. Salinger's stories. As writers, we have choices to make in what to leave in and what to cut. This is usually done in revision and with the help of a trusted reader, editor, agent, honest friend, etc. as to what works best for the story. They may not all be successful choices, but you make them for the sake of the work, making it the best you can and standing by those decisions.

Names:

Characters with the names “Sequoya”, “Rosemary”, and “Echota” appear across your novels (The Devil is a Southpaw, Where the Dead Sit Talking, The Removed). Why is this? Are these the same characters, do their names have larger metaphorical or historical significance, or is there something else that you are hoping the reader might take from this repetition?

They're a fictional family of characters who are all related. I like writing about this Echota family. Sequoyah from Where the Dead Sit Talking makes a brief cameo in The Devil is a Southpaw, in Part 3, because he's Matthew's cousin and is at his house. They're related to the Echota family in The Removed. I chose the name Echota as a nod to the historic site, New Echota, which served as a capital of the Cherokee Nation before the Trail of Tears.

About You:

“Brandon H.” makes a short appearance in The Devil is a Southpaw. Is this you (as if you’ll tell us 🙂 ). The more I read of your work, the more I want to learn about you, the author. I believe you have worked in juvenile detention centers. Might you also have had some personal experiences, say, during your childhood or adolescence that were particularly impactful and have informed your plots, characters or settings (including but not limited to perhaps any stints of incarceration 🙂 )? Have you ever thought about writing a memoir? How are Matthew and Milton inspired by people in your life and/or parts of you?

I have no interest in writing a memoir and feel reluctant to talk about myself much except to say I grew up and lived in Oklahoma my whole life. I've lived in New Mexico the past seven years because I teach here, though I would like to return to my homelands. I did social work and worked with adolescents twenty-five years ago, before I got a PhD and pursued an academic career.

Children's Writing:

When writing for adults and then writing for children how do you shift your writing style to find the appropriate voice for your characters? Are there any research or writing techniques that you employ to find authentic voices for your characters so that they resonate with your respective audiences?

Finding the voice can take a while, but once the characters are in my head they seem to talk very clearly, and I get to watch and know them well enough that I hope I can give them life on the page in a way that's interesting.

Closing Questions:

Why did you have to write The Devil is a Southpaw?

I’ve always loved postmodern and avant-garde novels, and I wanted to do something creative but also serious and fun. Serious art is where complex and difficult questions are made human and uncomfortable, especially in times of conflict and tragedy, impending doom, when most people don't like to feel uncomfortable. My hope is that this novel reflects important themes of trauma from incarceration, mental health, the toxicity of pride, and creates a novel in an artful and compelling way.

What advice do you have for early-career Indigenous writers, especially today, given all the uncertainty in our world, and, in particular, in the future of publishing?

If you’re a writer, you might think about Chekov’s idea: what are the important questions you think about? Use those as a starting point for your story. I think people are more interested now than ever before in hearing Native stories--of families, ancestors, history. Stories of colonization and independence and what it means to be a part of something beautiful and sacred. William Faulkner said, “a writer needs three things: experience, observation, and imagination—any two of which, at times any one of which—can supply the lack of the others.” Dr. N. Scott Momaday says in House Made of Dawn, “the simple act of listening is crucial to the concept of language, more crucial even than reading and writing, and language, in turn, is crucial to human society.” So learning to be a good listener is just as important. It's probably more important.

Dr. Brandon Hobson is the author of the acclaimed adult fiction novels The Devil is a Southpaw (2025), The Removed (2021), Where the Dead Sit Talking (2018), and other books. He also authored The Storyteller (2023) for children. The Devil is a Southpaw was recently announced as a finalist for the 2026 PEN / Jean Stein Book Award! He was also a finalist for the National Book Award, finalist for the St. Francis Literary Award, and winner of the Reading the West Award. His fiction has won a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in the Best American Short Stories 2021, McSweeney's, American Short Fiction, Conjunctions, NOON, and in many other publications. Dr. Hobson is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation Tribe of Oklahoma and Associate Professor of Creative Writing at New Mexico State University. We are also so very lucky to have him on staff here at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, as a beloved Writing Mentor.