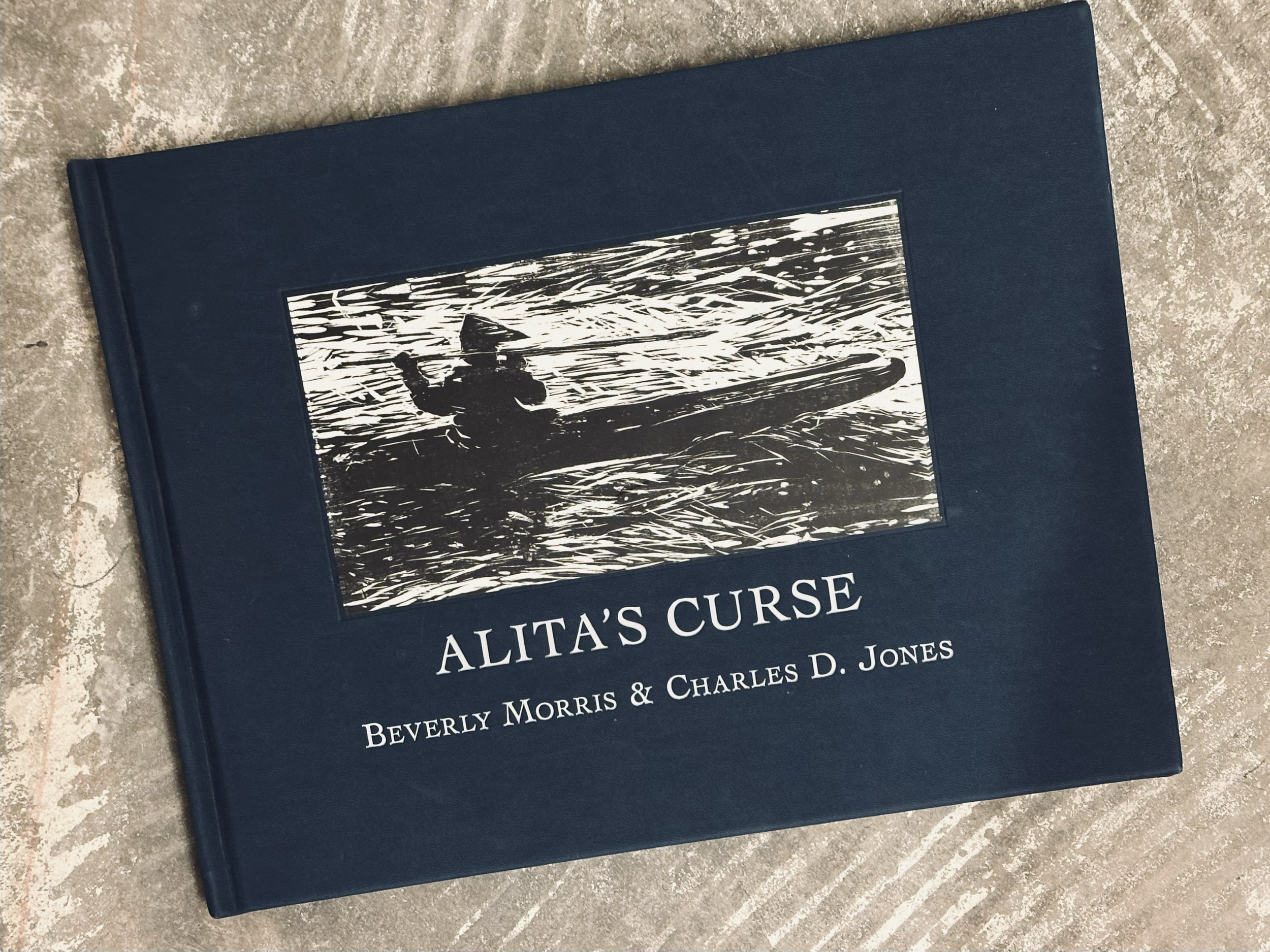

Alita’s Curse: A Review

By Beverly Morris

Woodcuts by Charles D. Jones

Stephen F. Austin State University Press, 2024

Some cultures begin by hardening the body against what is coming.

Among the Diné, babies are introduced to the season’s first snow, to prepare them for the winter ahead. In Alita’s Curse, Beverly Morris describes a similar Unangan practice:

“Each day the boys bathe in the chilling waters of Iliuliuk Bay to toughen them up for the long hunting journey ahead” (5).

These early rituals, quiet, practical, loving, anchor the book in a world where survival is taught through repetition and cold water, through hands and weather. Morris opens her story with Unangan practices: regalia, hunting tools, daily movements shaped by sea and ice. Culture is not explained; it is lived.

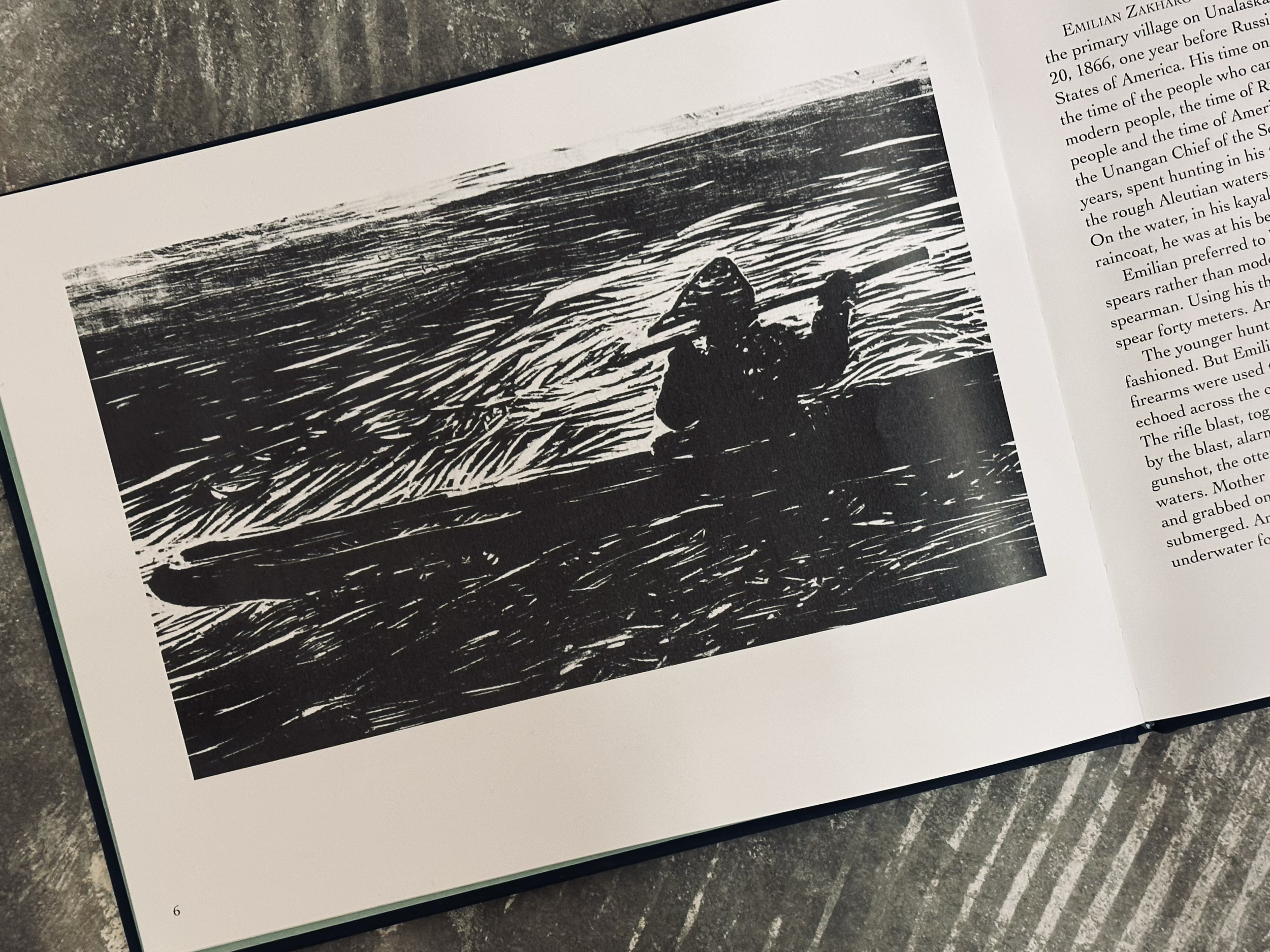

The fictional story of Alita’s Curse is based on the 1904 sea otter hunt and the loves of Morris’s great-grandparents, Alita Kochutin-Berikoff and Emilian Z. Berikoff. It unfolds across the Aleutian Archipelago, a chain of islands separating the Bering Sea from the Pacific for over 9,000 years. Time here is oceanic, not linear.

The fictional Alita is rooted in a real woman, Alita Kochutin-Berikoff, Morris’s great-grandmother, whose mother died when she was a young girl and whose father lived a long life. Alita later lost two children and three husbands. She lived through World War II, when the U.S. government exiled and interned more than 400 Unangax people.

by Chris Hoshnic

In Alita’s Curse, Emilian is preparing for the season’s sea otter hunt. Here, families were confined to abandoned fish-processing warehouses; single rooms without plumbing, furniture, or adequate food. This lasted three years. Survival, again, was not metaphorical.

When Father Martynov enters the story, tension between those Unangan lifeways and the colonial frontier sharpens. Conversion does not arrive cleanly; it arrives layered, worn beneath clothing, stitched into contradiction:

“Many of Emilian’s kinsmen wore Orthodox crosses under their garments, but he still wore his amulet” (10).

Alita’s Curse is a book about memory at war with imposed reality, about church, Russian Orthodox, and the slow pressure to forget. Alita and Emilian embody two responses to this erasure. The feminine clings and carries; the masculine loosens, drifts, mourns. Morris renders this imbalance gently, without accusation, as something inevitable and heartbreaking:

“The words of her songs were not from the hymn books, but the Unangan women understood the words” (17).

These songs are not nostalgia. They are survival.

The book itself is a crafted object, originally a fine press book and an edition of 35, was created by Charles D. Jones and Beverly Morris at Crazy Creek Press in Nacogdoches, TX. The trade edition is now available at Amazon and Barnes and Noble Books.

The version I had, was printed on Gutenberg paper using Cochin, American Uncial, and Ultima typefaces from photopolymer plates on a Vandercook 215 proof press. Charles D. Jones’s woodcuts, imagined by Morris, appear throughout, lending the book a whimsical, almost childlike quality. This is not naïveté, but a deliberate return to visual storytelling, to the engraved line.

Engraving, image-making, has helped keep Unangan memory alive when other systems failed them. The book’s structure honors this truth. Writing, after all, is a colonial technology introduced to Indigenous peoples, often used to misname and diminish them. Morris is keenly aware of this tension. She places image at the foundation of her storytelling, allowing the visual to carry what words alone cannot.

Alita’s Curse ultimately asks necessary questions: How do Indigenous stories arrive to us? Who stands at their center? Who are they given to, and who is allowed to hold them?

Morris does not answer these questions outright. She engraves them instead, leaving their lines pressed deep into the page.

Beverly Morris (Aleut) is producer, director, and owner of Chain Reaction Productions. She has been associated with the IAIA since 1988 as a student, staff member, producer, and director. Morris received her BFA from Stephen F. Austin State.